“Everything is but discourse until his Majesty gives his consent”: this statement made by Sir Thomas Roe, an English diplomat in 1636 [1], may seem a little tongue in cheek but it provides some truth as to how the Privy Council operated specifically during the reign of Charles I. For more than a decade in 1630, Charles chose to rule the realm without Parliament after bitter disagreements prompted Parliament shutting in 1629. As a result the Privy Council took on a more central role in government, functioning as the chief body through which Royal order, administration and policy was channelled.

Yet many individuals today do not realise what the Privy Council is and the central role it has in fact played in our nation’s history. This remarkable institution of government is one of the longest surviving institutions of English and British government spanning over 1000 years! To understand the Council’s functions under Charles I we must first look at what it actually was.

A Council of Many Monarchs: Origins and Development

Traditionally the ‘Privy’ Council, not referred to as such until the 15th century, consisted of advisers drawn from the nobility and church (many also serving in government) who would advise and assist the monarchy in matters of state. The Privy Council had its origins in distant Anglo-Saxon times. The Witenagemot or Witan was a council and forum comprised of leading aristocracy and churchmen providing advice to Anglo-Saxon kings. The development of this advisory council to the King led to an increase in the Council’s role as an instrument of Royal administration and Royal justice. By the 16th and 17th centuries the role of the council in Royal government had reached its pinnacle with a growing amount of business being handled by the Council at the monarch’s bidding.

The council’s judicial arm had also grown as petitioners increasingly sought royal justice that could not be obtained through the usual legal channels. Separate courts were created in the 15th century in order to handle many of the petitions and disputes. These were the Court of Star Chamber and the Court of Requests, both attended by certain members of the Privy Council.

A Council of many Talents: Varied Business of the Council under Charles I

King Charles took a personal interest in the business of his Privy Council as he did in the wider running of royal government during his reign. Charles regularly attended meetings and directed Council decision making on many important issues though his Council would also deal with matters independently.

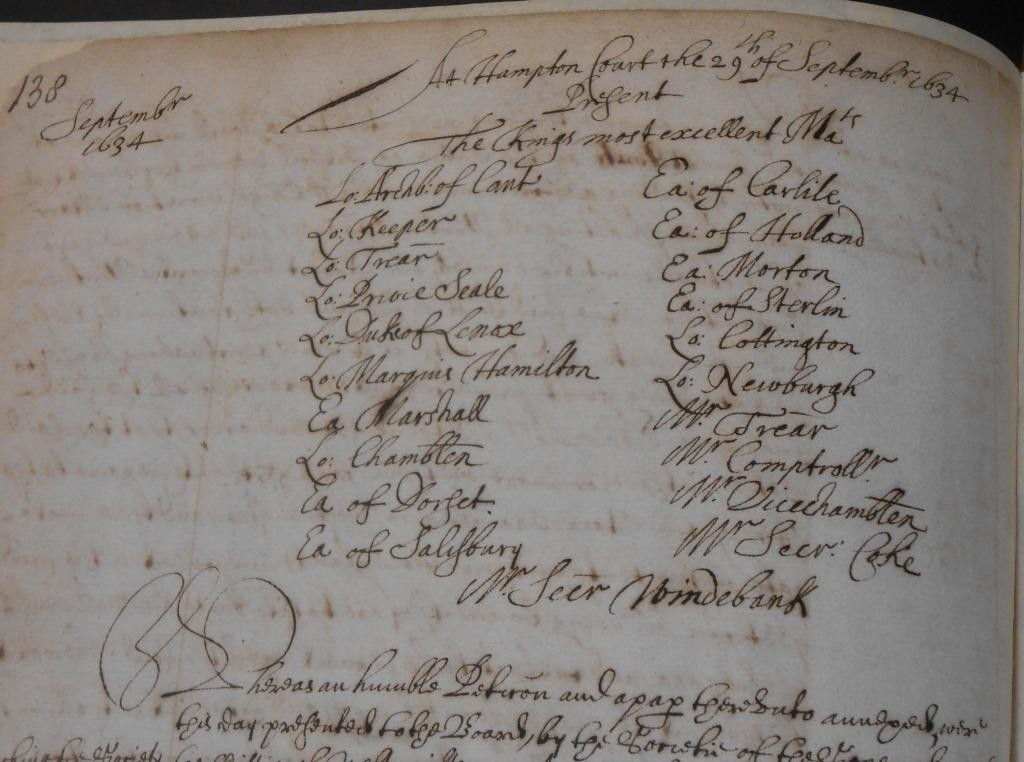

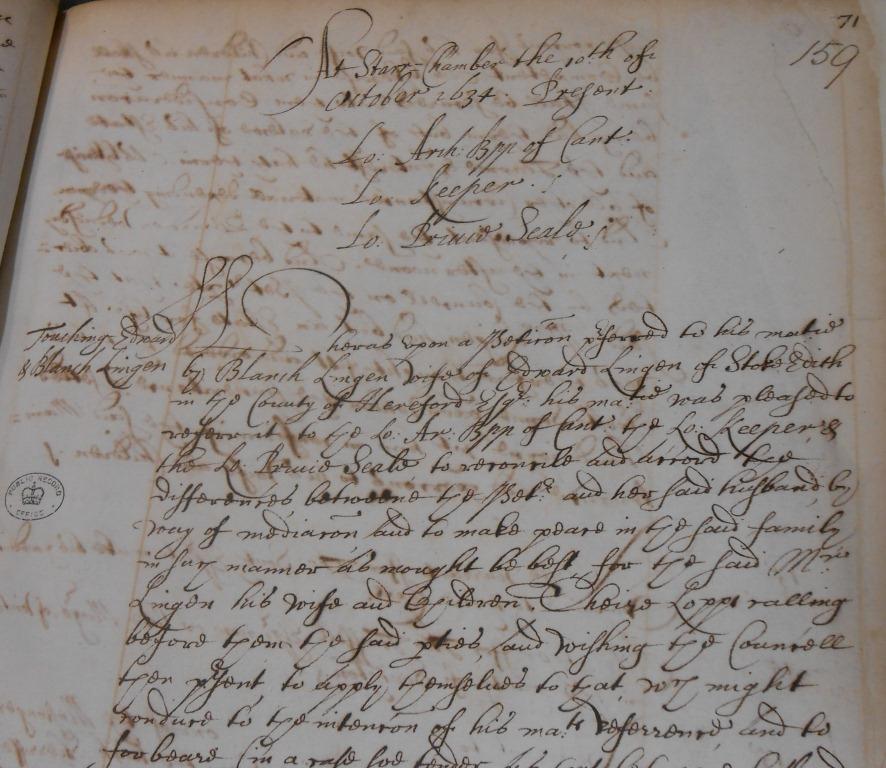

Turning to the orginal records, the registers of the Privy Council held at The National Archives in PC 2 are the main series of documents to shine a light on the business of the Council. These registers provide a summary of actions the Council took on a regular basis for a wide variety of issues, disputes and complaints. Below a series of examples drawn from the Privy Council of Charles I in the 1630’s are explored during what became a unique period in the history of the Council.

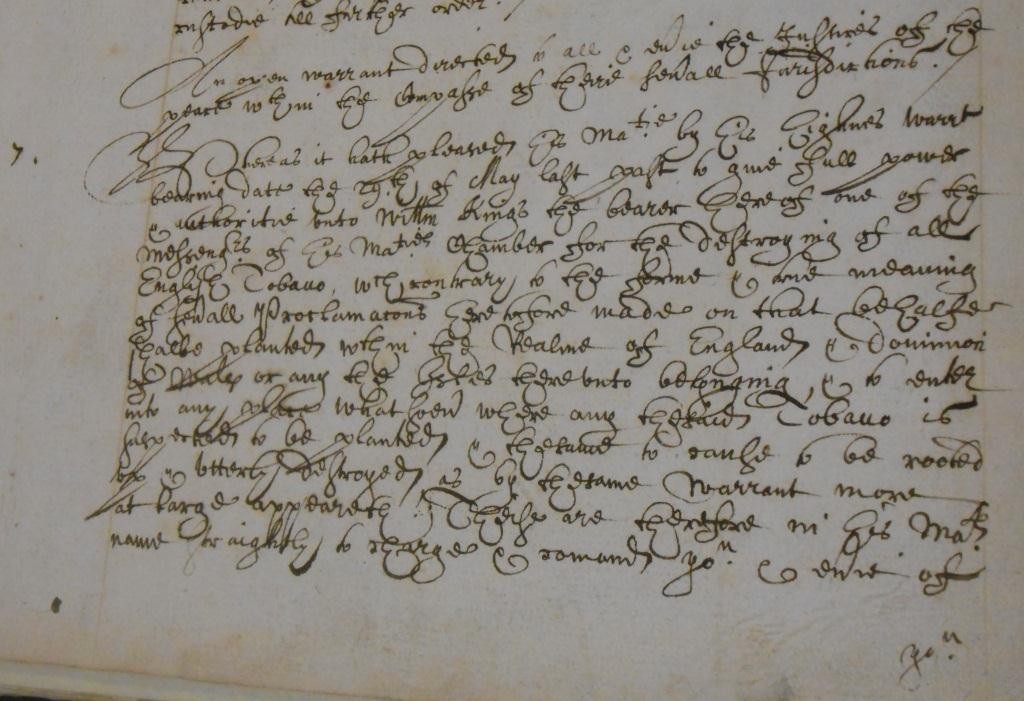

In the absence of Parliament, the Privy Council became the forum for issuing and enforcing law and order through royal proclamations which the council also helped to enforce. One of the recurring themes in the registers of 1634 is the illegal growing of tobacco in the British Isles! The problem was widespread enough for the Council to order the issuing of an open warrant:

The 1630’s also witnessed a process of centralising of government powers and increasing of accountability of Justices of the Peace – the king’s judicial representatives in the localities. Therefore a surprising amount of council business consisted of exchanges about specific local and regional affairs.

We also find letters from the Council to Justices of the Peace giving instruction usually on behalf of a petitioner or in order to authorise or pressure action against abuses of Royal proclamation. For example, on 31 August 1634 letters were sent to several Justices of the Peace for Middlesex instructing them to investigate whether according to petitioners heard by the Privy Council, a certain William Long kept a tavern illegally within Covent Garden.

Delving deeper into the registers we discover that the council dealt with quite a random and miscellaneous array of business from domestic economic matters relating to involvement in local "infrastructure" project, for example:

Soap boilers in the city of Bristol who were making undeclared profit from selling soap cheaper than licenced to make and were ordered to pay to the king £4 for every tonne. They are additionally not permitted to sell their goods outside Bristol except in counties further westward and beyond the river Severn. [2]

In an example of the board’s contribution and concern for updating and repairing of local infrastructure, the Council lent its support to calls from locals in Blackney, Norfolk for the quay to be urgently repaired and also that the river channel should be scoured as requested.

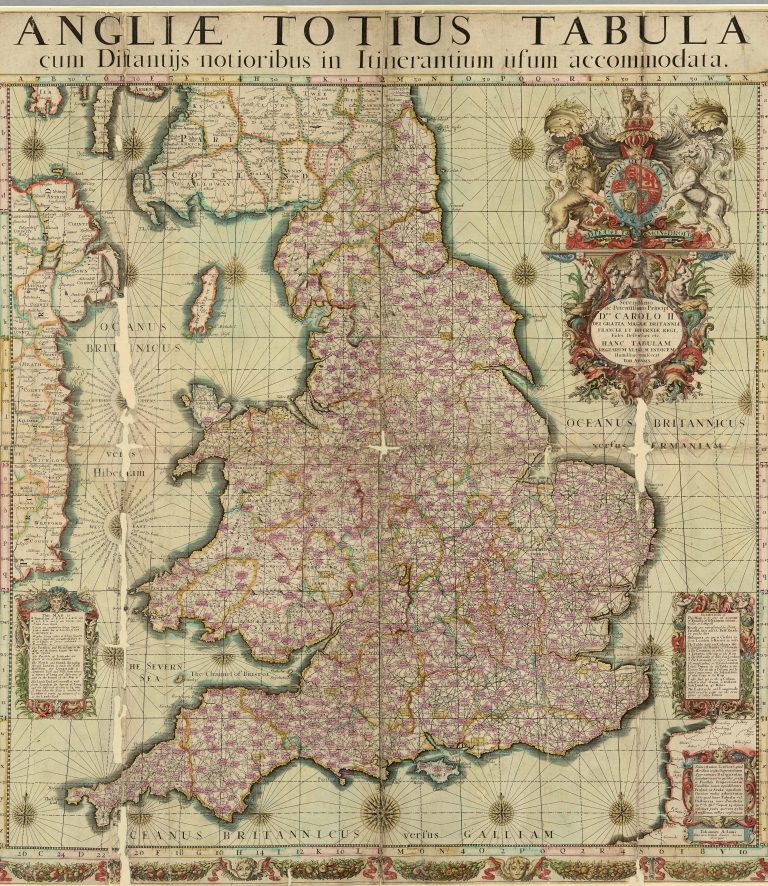

The council also authorised travel abroad by issuing passes many of which were granted to soldiers and officers who were volunteers in the Protestant armies in Germany or fighting with Protestant Dutch rebels in Holland against Catholic Spain.

Passes were issued on the 18th July, 1634 for Sir Patrick Ruthin, General, Sir John Ruthin and Alexander Coningham, Colonels and Robert Steward, Lieutenant Colonel, to return to Germany to their commands. These are likely to be Scottish officers given that many Scottish volunteers were serving in the armies of the King of Sweden in Germany at the time. We even see that wives of husbands who were soldiers, diplomats or merchants abroad were given licence to go and visit them.

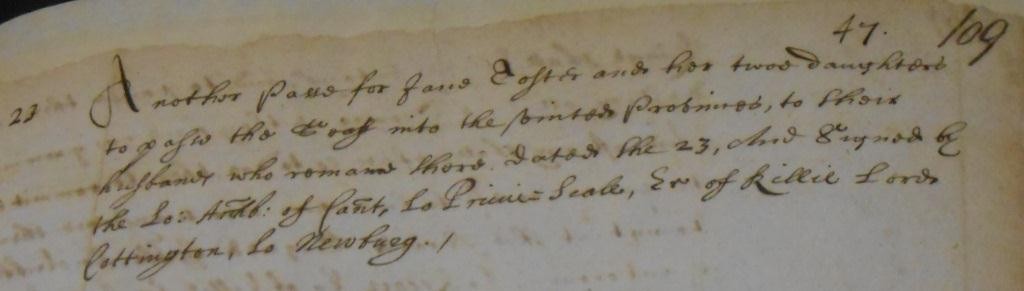

On 23rd July, Jane Toster and her two daughters were granted a pass to travel to the Dutch United Provinces to see their husbands there.

Alongside all these issues we see the Council adjudicating on disputes filed by petitioners that include a family squabble over custody of a child and petition for an increase in alimony payments by a wife from her husband! [3]

In the example below the council were called to mediate in a dispute with petitioner Blanche Lingen and her husband Edward Lingen, esquire, of Stoke Edith in Herefordshire over provision of sufficient maintenance and allowance by Edward Lingen from his estates for his wife and children. The council agreed that Edward should have possession and management of his own estate but that sufficient allowance should be provided for his wife and children. The terms and extent of this provision was to be determined and recorded in case of breach at a further session of the council to be attended by Edward, with his eldest son and inheritor.

Decline and Survival

The start of the English Civil War marked the beginning of the decline of the Privy Council and the abolition of the Courts of Star Chamber and Requests. As the institution of monarchy gave way to Parliamentary sovereignty, the Privy Council became increasingly honorary.

Today it is still a functioning body consisting of leading politicians drawn from the House of Commons and the House of Lords providing advice to the Queen. Though a shadow of its former self, the survival of the Privy Council today is a testament to the important contribution it has made to the rich history and evolution of British government.

[1] Calendar of State Papers Domestic Charles I Vol. 10: 1636-1637, p. 250.

[2] PC 2/44, pp.104-105.

[3] Ibid., p. 83; pp. 22-23.

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.