The independence of many South American countries from Spanish and Portuguese rule followed uprisings and wars from 1806 to the mid-1820s. British diplomacy in the independence of South America was, generally, about trade. Britain was an ally with Portugal and their commercial and navigation treaties gave British trade access to Brazil. Spain was an enemy for most of the 18th century, and refused trade routes with anyone other than Madrid.

European War

The alliance against Napoleon Bonaparte and France was not a united front. Austria and Russia fought to safeguard their territory; Britain fought to protect her Naval supremacy and her expanding Empire and the associated trade.

Napoleon aimed to stop Britain trading, especially with Portugal and her colonies. He made Portugal's King Dom Joao VI an ultimatum: stop trading with Britain; close ports to English ships; imprison all British subjects in Portugal; and seize all British assets and merchandise. Failure to comply would result in a French invasion of Portugal.

Britain's response was to threaten to sink the Portuguese fleet in the Tagus, and seize colonies, if they complied with Napoleon's threat.

Metropolis or Colony

Dom Joao chose self exile, and was escorted by a Royal Navy fleet to Brazil, in November 1807. Rio de Janeiro became the Metropolis 1, Portugal the Colony, resulting in the growth of trade and prosperity for Brazil. The British Ambassador, Lord Strangford, remained with the Royal Court during Dom Jaoa's exile: negotiating treaties, restraining Portuguese forces from invading the Banda Oriental, and pushing for the Royal Court's return to Portugal after the war.

Strangford returned to Europe with the Royal Court in 1822. The Cortes2 in Lisbon pushed for Brazil to return to Colonial Status. This resulted in Rio de Janeiro looking at independence, not in objection to Portugal, but to ensure their own finances and security.

There was one trade Britain wanted outlawed: slavery. Britain was against the slave trade, but this stood against their agreements with Portugal. A large percentage of the Brazilian income was from the slave trade, but they were to cease the trade in slavery, north of the equator.

Brazil declared their independence in November 1823 and Portugal eventually signed a Treaty, mediated by the British, in August 1825 recognising Brazilian independence. By 1830 the slave trade in Brazil was illegal.

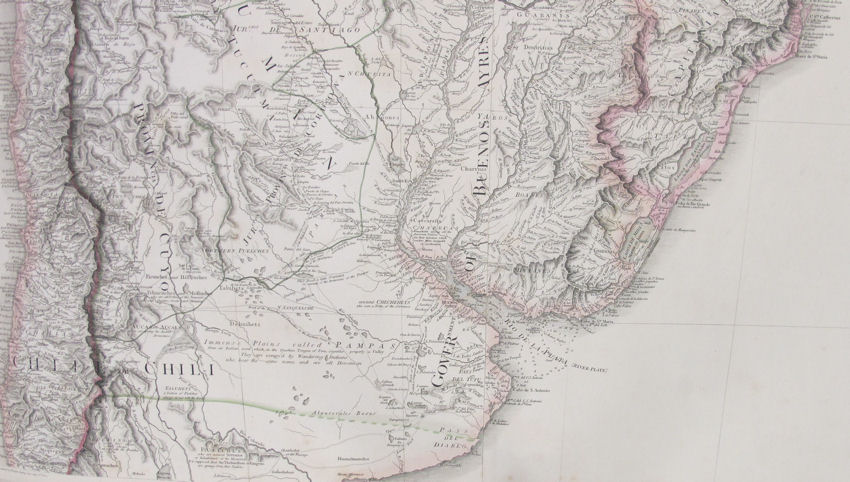

Battle of Buenos Aires

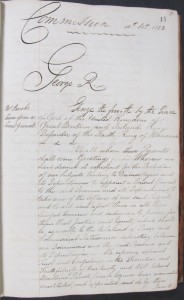

Napoleon's attempts to cut off Britain’s trade, and thus their war effort, led the Admiralty to discuss South America in 18042, but no decision was made on how to gain a trading foothold on the continent. Sir Home Popham forced their hand in 1806, having led a successful naval force to the Cape of Good Hope to recapture the colony from the Dutch.

Popham convinced Lieutenant General Sir David Baird to send a force under the command of Brigadier General W G Beresford to capture Buenos Aires from Spain, believing the inhabitants of the Rio de la Plata would welcome the British.

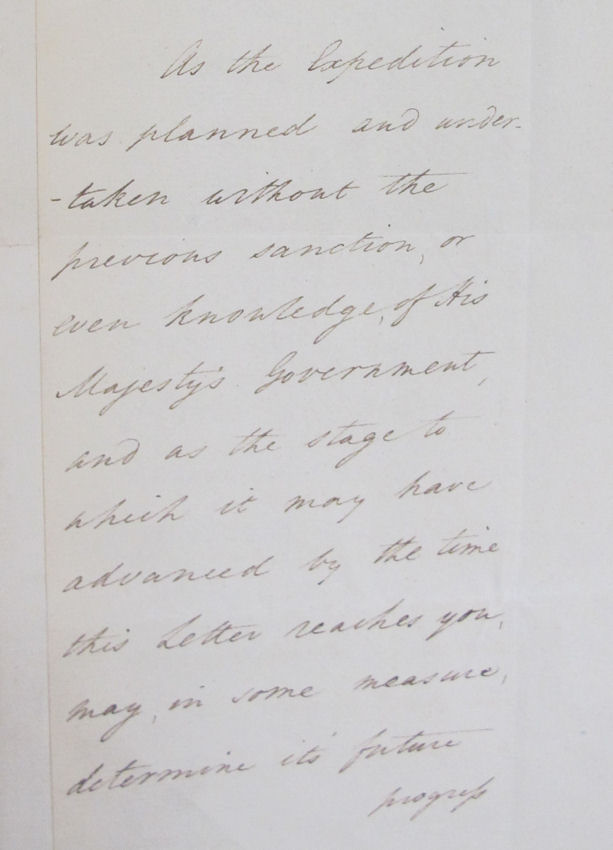

William Windham, Secretary of State for War, reply to the invasion was: ‘the expedition has been undertaken without the previous sanction or even knowledge of His Majesty’s Government’.

Beresford successfully entered Buenos Aires on the 12 July 1806. Reinforcements were sent, under the command of Brigadier General Sir Samuel Auchmuty. On their arrival they found the British force had capitulated and had been captured as prisoners of war. A militia force under the command of General Santiago de Liniers 3, had retaken the city on the 12 August 1806.

Lieutenant General Whitelock attempted to capture the city in 1807, but again the defendants defeated the invaders, with the British force again capitulating to Liniers.

Independence

This event may not seem much like Britain influencing a rebellion against the Metropolis, but it gave the South Americans belief they could. The British were defeated, not by a Spanish army, but the local Creole militia. Furthermore, if a powerful nation such as Britain could lose one of her major colonies in North America, where did that leave South America and Spain?

The independence of North America had the support of France and Spain, but these countries were fighting each other in Europe. North America was struggling to become a Power of its own, and by 1811 the United States America and Britain were at war.

In South America, Napoleon's invasion of Spain raised the question of who was their master, Spain or France? This led to attempts at self-governing, and a fight to control the regions. Various juntas, or political groups, rose and fell. Initially the intentions were to remain self governing colonies of Spain, but it soon spread to calls for independence.

There was no single national identity; South America was home to the indigenous; the slave; and the Spaniard. The Viceroyalties of New Spain; New Granada, including Central America; Viceroyalty of Peru, including Chile; and the Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata, remained in a state of civil unrest. Buenos Aires marched on Peru; Brazil and Buenos Aires fought over the Banda Orient.

By 1814 Britain and Spain had become allies, and British influence in South America was indirect. Britain wanted trade, so they neither acknowledged nor denied independence.

Britain's position began to shift in September 1823 when London wrote to Madrid informing them of the plan to send consular officials to South America and the newly independent states. Chile gained independence in 1818, and Ecuador in 1820, Venezuela 1821, and Peru in 1824. It wasn't until the 1850's that Spain fully recognised South American independence.

Individual influence

Other ‘British’ influences in South America relied on the contributions of individuals. Spain employed Irish people for many diplomatic and military positions. One was Ambrose O’Higgins who became the Viceroy of Peru. His illegitimate son, Bernado O’Higgins, helped Chile to their independence, and became Supreme Director of Chile. Bernado O’Higgins also later helped Bolivia win their independence.

A disgraced former captain in the Royal Navy, Lord Cochrane, organised the Chilean Navy, and then Brazil's, helping them achieve naval supremacy in South America.

British merchants cut the monopolies held by the Spanish elite. With the increase in merchants came an influx of new ideas and new people from Europe, including academics and artisans and tradesmen. With Brazil opened up to new ideas, and the increase in Europeans across the entire South Americas, Britain's goal to increase trade had influenced a continent's fight for independence.

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.

2 comments

Comment by Alejandro Milberg posted on

Working on the correspondence of William Porter White, an American merchant who is credited by some Argentine authors as being the one who gave Sir Home Popham the idea for the 1806 invasion of Buenos Aires, I came across a reference to an unnamed British war frigate, anchored off Valizas (currently Uruguay), captain MacDugal, first lieutenat Mr. Purchase, where Mr White sough asylum in November 1815 and on board of which he remained for several months. Would this information be enough to locate this vessel and to find out what its mission was? Thank you!

Comment by Keith Mitchell posted on

Alejandro,

The correspondence of the War Office in the National Archives catalogue reference WO 1/161, has a letter to Sir Home Popham from a Mr F Waine regarding the state of affairs in Buenos Aires. Although Popham may have received other correspondence from merchants trading in Buenos Aires and Montevideo

To locate the ship you would need to search all Officers with the names McDugal and Purchas, or variants of those names, to establish the vessel they were both on in 1815. This will take time. The Log Book would establish what they were doing.

This guide will explain how to trace Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the Royal Navy: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/royal-navy-commissioned-and-warrant-officers-further-research/

Before visiting The National Archives read our webpages: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/about/visit-us/