Winston Churchill in a speech in the House of Commons in October 1943 famously described the unique and ancient friendship between England and Portugal as an alliance “without parallel in world history”.[1]

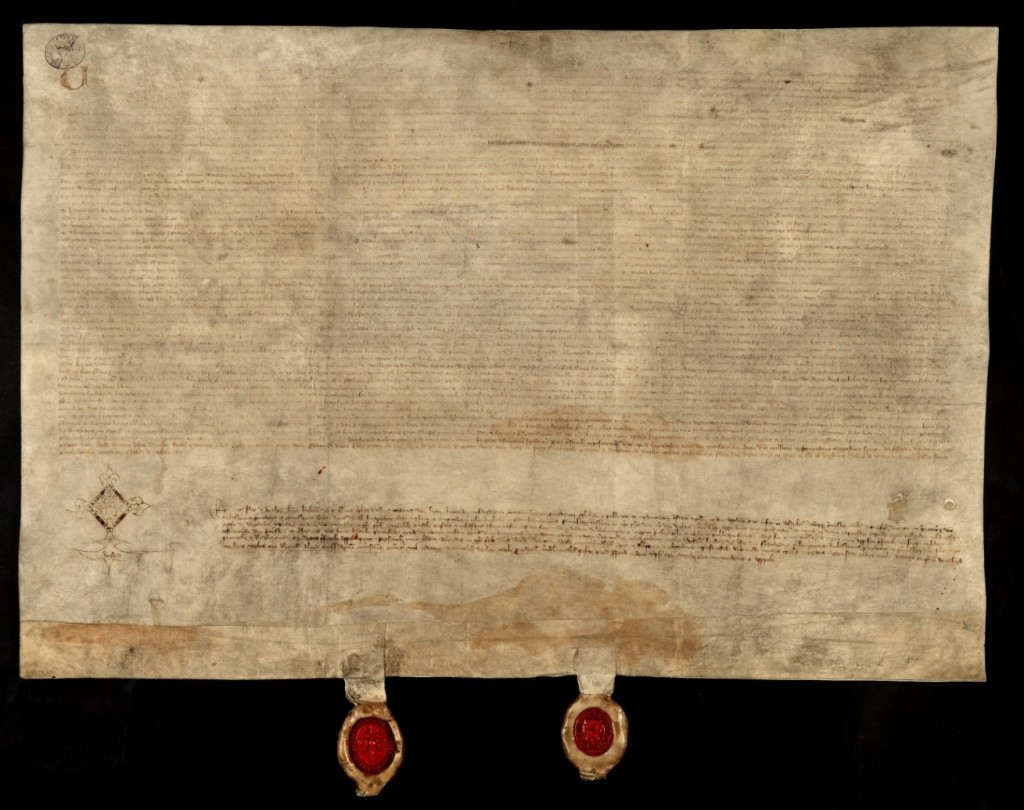

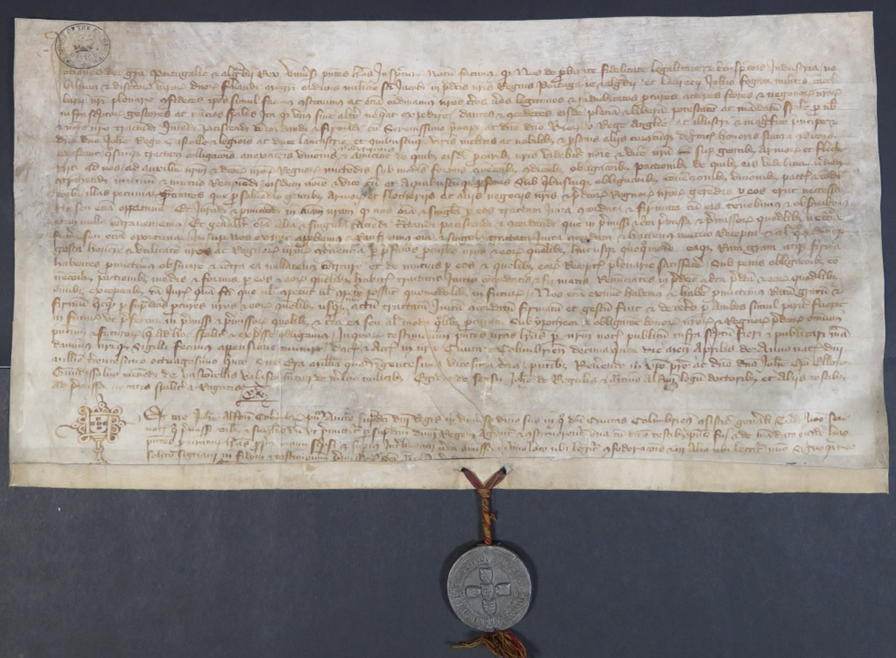

It is 630 years since a treaty of alliance between King Richard II of England and King John I of Portugal was ratified at Windsor on the 9th May 1386 (The National Archives: E 30/310). Though it is not the earliest of the Anglo-Portuguese treaties that survive, the Treaty of Windsor is significant because it effectively cemented and strengthened ties between the two kingdoms and helped convert a fledgling alliance into a more permanent legacy of history.

The terms of the treaty included provisions for guaranteeing the mutual security of both nations and strengthening of commercial ties such as the right of both countries to trade on the terms enjoyed by the subjects of that country. There were even clauses encouraging freedom of movement and settlement between the two countries, as subjects of either country had the right to dwell in the domains of the other.

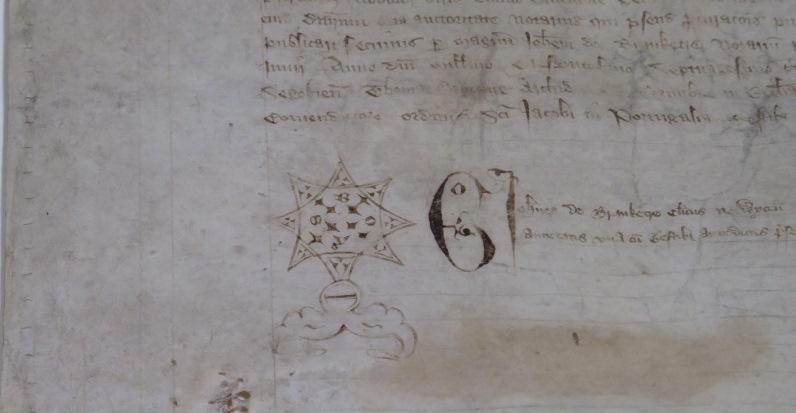

The seals attached to the document are those of the Portuguese ambassadors: Ferdinand Afonso de Albuquerque, Master of the Portuguese military order of St James and Chancellor of Portugal Lawrence John Fogaca entrusted as plenipotentiaries in the treaty negotiations.

So how did this alliance - the longest continuing alliance in global history - transpire?

Origins

The Anglo-Portuguese alliance had in fact been born primarily out of converging strategic interests. An alliance between France and Castile (precursor to the kingdom of Spain) in 1369 had caused consternation at the English court. Fourteenth century Anglo-French relations mostly alternated between hostile rivalry at best to periods of open conflict and war at worst. Through the alliance with Castile, which had one of the largest fleets in Western Europe, France could utilise Castilian sea power, in its struggle against England. Therefore closer union with Castile’s western neighbour Portugal was a logical step to counter this threat. Added to this was a dynastic interest as the Duke of Lancaster, John of Gaunt, had a legitimate claim to the throne of Castile through his wife, Constance, daughter of Peter the Cruel (1334-1369).

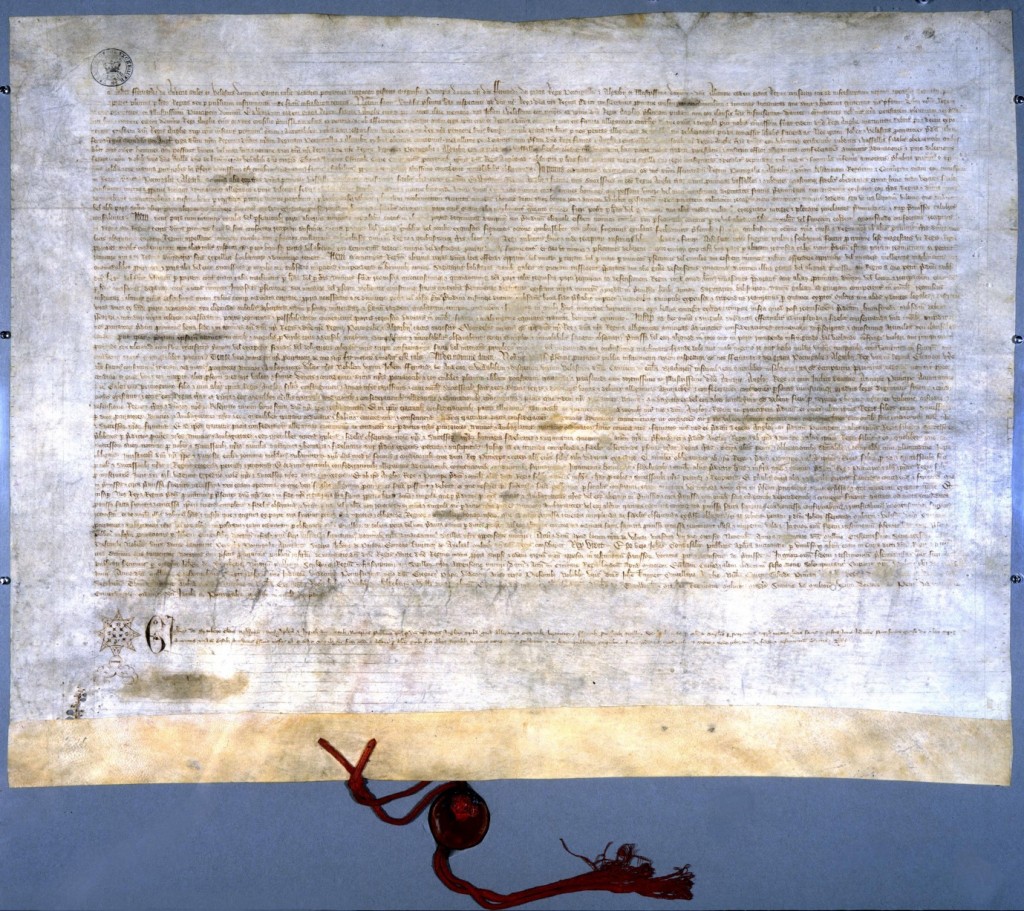

Below is the treaty of alliance sealed in 1373 between King Edward III and King Ferdinand I of Portugal (The National Archive: E 30/275).

It was believed the answer to the strategic stalemate lay in the “Chemyn de Portugal” and the “Chemyn d’Esapigne” the “way of Portugal” and the “way of Spain” a reference to the policy of military intervention in Iberia. With military victory in the Iberian Peninsula and a Plantagenet on the Castilian throne, it would only be a matter of time before France would be forced to the negotiating table.

However the alliance and Portuguese independence itself was soon under threat of becoming extinct in the early 1380s.

England had already sent a failed expedition to Portugal in 1381-2 under the duke's brother Edmund of Langley in an attempt to push Castile out of the war. It was even detrimental the hitherto close Anglo-Portuguese ties. Undisciplined English troops had caused outrage by raiding Portuguese towns and killing inhabitants whilst exclusion from Portuguese-Castilian peace negotiations in 1382 drew English resentment.

This was shortly followed by a political crisis caused by the death of King Ferdinand of Portugal on 23rd October 1383. Ferdinand’s son in law was the Castilian King John I who began stripping away Portuguese independence in favour of political and dynastic union with Castile. Portuguese nationalist opposition rallied around King Ferdinand’s half-brother John of Aviz and resistance quickly escalated into civil war.

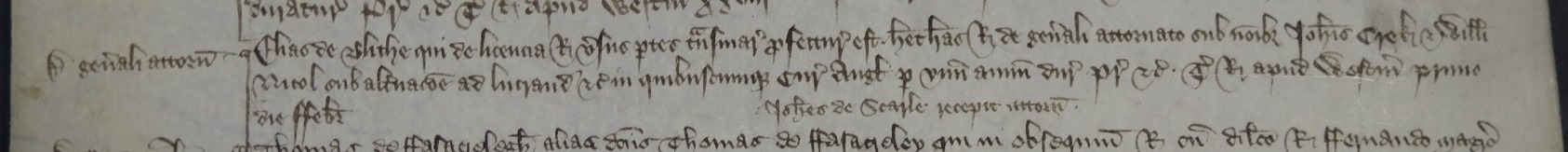

John of Aviz was desperate for outside military help and sent ambassadors to England to request permission to recruit soldiers there. The Portuguese ambassador Ferdinand Afonso de Albuquerque, Master of the Portuguese military order of St James succeeded initially in raising only a modest force of approximately 800 Anglo-Gascon troops. Nevertheless these soldiers would play a laudable role in the eventual defeat and withdrawal Castilian forces from Portugal particularly in their contribution to the victory over Castilian troops at the battle of Aljubarrota (14th August 1385). Below is a record of the attorneys appointed by the esquire Elias Blithe, who was named by a Portuguese chronicler as one of the leaders of the Anglo-Gascon contingent.[2] He appointed John Creke and William Nicol to represent him in any legal disputes that may arise whilst on military service.

Running concurrently with military efforts were diplomatic measures orchestrated by John of Aviz, to ensure that Portuguese independence would survive. Ten days after his coronation on 15th April 1385, he had instructed his ambassadors to negotiate an alliance with Richard II of England and to raise much needed loans to pay his troops.

A breakthrough regarding these negotiations was slow in coming but a shift in policy towards Iberia, and the growing threat of a Franco-Castilian invasion in early 1386, created an English appetite for reaffirming its alliance with Portugal. The Duke of Lancaster was also planning an expedition to Castile for the summer of 1386 and Portuguese military assistance would be almost essential. To sweeten the deal and demonstrate he was a serious ally, John agreed to dispatch a squadron of ten Portuguese galleys to be stationed in English waters to bolster protection of English shipping and England’s south coast (The National Archives: E 30/309).

On 9th May 1386 the original draft (protocol) of the treaty was produced and ratification of the treaty was enrolled in the 'Treaty Rolls' records in the office of Chancery finally on 1st December 1386 (The National Archives: C 76/71 m.9).

Legacy

In the short term the military objectives of the alliance concerned with neutralising the Castilian threat to England and indeed Portugal failed. The duke of Lancaster’s expedition was ultimately fruitless and he sued for peace with John I of Castile in exchange for a generous pension. With the strategic and dynastic motive for the alliance removed (at least from an English perspective), the alliance with Portugal was temporarily sidelined.

The reason that the alliance did not fizzle out was the marriage of Philippa, daughter of the duke of Lancaster to John I of Portugal in 1387 which added a crucial dynastic element to the alliance between the two kingdoms. Moreover the two nations were enjoying the commercial benefits that the treaty endorsed. Portuguese government records, for instance, show that the city of Oporto was profiting from the trade in cloth and a wealth of other commodities from England passing through its port and gates.[3]

There is also evidence of settlement encouraged by the treaty in England during the 15th century from ‘alien’ subsidy records incorporated into the England’s Immigrants: 1330-1550 Database. There are 20 individuals identified as Portuguese listed in the alien subsidies for the 1440s in the National Archives record series E 179.

Perhaps the biggest legacy was the successful adherence to terms in the treaty of Windsor that supported mutual military assistance and security. Although not invoked until several centuries later, the terms of the alliance were to be called upon during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries when Portuguese independence was again threatened. In 1762 Anglo-Portuguese forces successfully defeated a Spanish invasion force and again during the Peninsula war of 1808-1814, Anglo-Portuguese troops under the Duke of Wellington thwarted Napoleon’s attempts to conquer Portugal, most notably at the battle of Bussaco (27th September 1810).

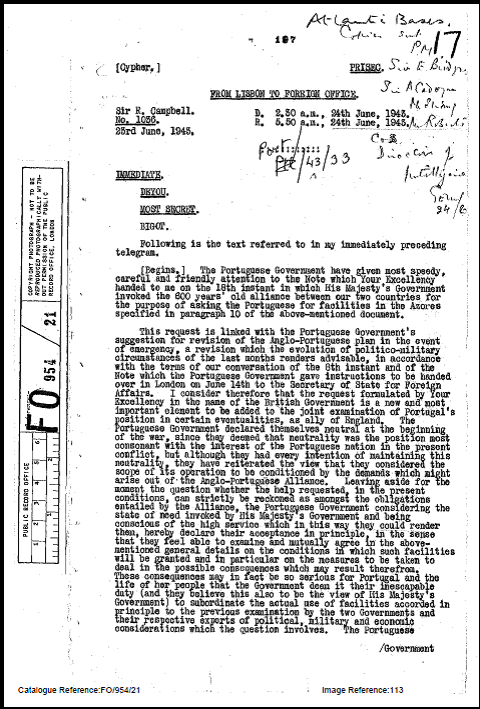

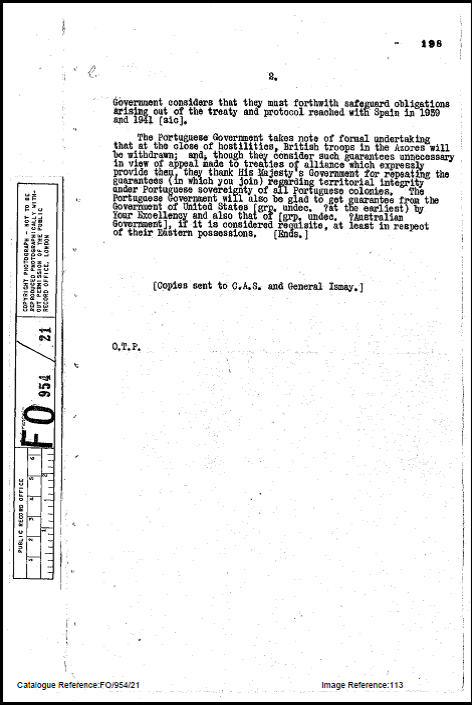

During WWII, Portugal proved that it was still strongly committed to the alliance. In spite of Portuguese neutrality, British ships were allowed to refuel in Portuguese ports and Portuguese planes participated in reconnaissance missions for the Atlantic convoys. Moreover in 1943 Portugal agreed to British and American air force squadrons being stationed in the Azores.

In a telegram to the Foreign Office dated 23rd June 1943, the British ambassador to Portugal Sir Ronald Hugh Campbell confirmed that the British government had invoked the 600 year old alliance between the two countries as a basis for requesting the use of military facilities on the Azores.

Forty years later these bases on the Azores were again requested in 1982 during the Falklands conflict (The National Archives: FCO 9/3607).

It is a testimony to the continued commitment demonstrated by both nations down the centuries to support one another that to this day the Anglo-Portuguese alliance is still a valid agreement endorsed by both countries and no doubt will continue to be in the future.

[1] House of Commons Debate, 12 October, 1943, vol. 392 cc716-19, published at http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1943/oct/12/agreement-with-Portugal

[2] Fernao Lopes, Cronica, ed. and trans. Lomax, D.W. and Oakley, R.J, in The English in Portugal 1367-87: Extracts from the Chronicles of Dom Fernando and Dom Joao, (Warminster, 1988), 47, p.171.

[3] Tiago Viula de Faria, ‘Tracing the ‘Chemyn de Portyngale’: English service and servicemen in Fourteenth Century Portugal’ in the Journal of Medieval History, 37 (2011), p. 265.

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.

2 comments

Comment by George Fergusson posted on

My grandfather's grandfather, a British sailor called John Pascoe Grenfell, spent several years in the 1820s and 30s on secondment to the emerging Brazilian Navy fighting (I think with HMG's approval) against the Portuguese. I have sometimes wondered how this activity fitted in with this Old Alliance. Any clue?

Comment by Benjamin Trowbridge posted on

Dear Mr Fergusson

Thank you for your comment. I have endeavoured to try and answer your query below providing some political background to British involvement and explanation for the service of British sailors and officers in the Brazilian Navy.

Political Background to British Involvement in Brazil in the early 19th century:

The underpinning of British policy in Brazil during the early decades of the 19th century stemmed primarily from safeguarding its trade. It already enjoyed substantial trade licenced under the provisions of Anglo-Portuguese treaties ratified in the early 18th century but which also of course had its origins in the Treaty of Windsor in 1386.

Trading privileges in Brazil had been secured from the Portuguese monarchy in 1810 at the height of the Napoleonic wars when Portugal was under threat of being incorporated into vast Napoleon’s empire. These were agreed in return for British guarantee of protection for Portugal and its colonies in the tradition of the mutual guarantees underlined in the original treaties of the late 14th century. The British government were committed to a position at first of mediation between Portugal and its colony Brazil in order to avoid any upset to the lucrative British trade enjoyed in the colony. To protect this maritime trade, a large British fleet was also stationed in Brazilian waters.

However the revolution of 1820 in Portugal triggered a drive for independence and the outbreak of armed conflict in Brazil. This event had the effect of altering British policy in favour of recognition of an independent Brazil. This policy once again was governed by self-interest and preservation of trade the guarantees of protection and security outlined in the Anglo-Portuguese treaties did not extend to internal revolution. Therefore Britain was able to pursue a policy of recognition and deemed it necessary to maintain its trading monopoly and the British government exerted some pressure on Portugal until it eventually agreed to recognise Brazilian independence itself in 1825.

Formation of the Brazilian Navy and Recruitment of British Officers and Seaman:

During the war of independence (1822-1825), it became imperative for Brazil to expand its army and particularly its navy in order to achieve military victory. Both sides saw naval dominance along the coast as a decisive factor in obtaining this.

However the shortages in reliable crews to man newly acquired or repaired warships meant that reliance was increasingly placed on the enlistment of British sailors serving in a mercenary capacity.

At the end of the Napoleonic wars there was large scale demobilization of sailors in the Royal Navy and a reduction in commissioned ships. British and Irish sailors and soldiers were however able to find employment as mercenaries in the ranks of the navies and armies of South America countries including Chile and Peru as well as Brazil. Brazilian recruiting initiatives were carried out in the ports of London and Liverpool during 1822 and 1823 with the informal permission of the British government. It is possible that your grandfather was either recruited in the service of the Brazilian Navy in this capacity and continued service after Brazil achieved independence or was posted to the Navy on secondment after independence. The Brazilian Navy itself was led by British officer Thomas Cochrane who had been instrumental in victorious revolutions in other South American Countries.

British support after Brazilian Independence:

It was in Britain’s paramount interests to offer support and protection to the newly independent Brazil being its primary trading partner. However it was upon Brazilian initiative that British sailors continued to be recruited into the Brazilian Navy which needed additional manpower during the string of conflicts that marked the first two decades of its independence. The government of Brazil for instance mounted a recruiting campaign in the Orkneys and Shetland Islands during 1836 when the Brazilians were trying to put down a rebellion in Para.

The Brazilian Navy was involved in other conflicts such as the Cisplatine War between Argentina and Brazil in the 1820s where it won victories over the Argentinian Navy and in fighting rebels on the lakes of Rio Grande do Sul in the 1830s. A lot of British officers and sailors forged careers in the Brazilian Navy such as Commander John Pascoe Grenfell.

I hope this gives you a thorough exposition and context for both British involvement in Brazilian affairs and the nature of recruitment of British sailors and officers in the Brazilian Navy. As the Anglo-Portuguese alliance did not cover internal rebellion and discord, British policy did not for the most part contradict the provisions of the treaty. After Brazilian independence the Anglo-Portuguese alliance no longer applied to Brazil with whom Britain was able to treat with separately.

Kind regards