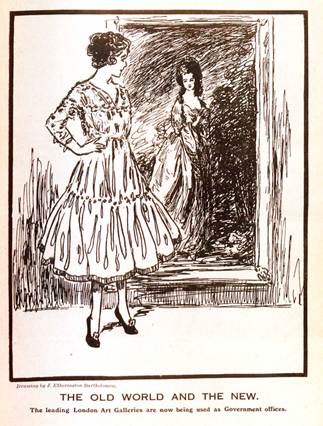

During the First World War there was a huge increase in the number of women engaged in areas of work which had previously been dominated by men. One of these was clerical work within the Civil Service.

Women had worked in businesses and offices prior to the outbreak of the war. Ray Strachey, who is now perhaps best remembered as the author of The Cause, one of the key early texts about the struggle for women’s rights in Britain, commented on this fact in 1936, in a book entitled ‘Our Freedom and its Results’. She wrote, ‘Between the last decades of the nineteenth century and the outbreak of the war there was …. a very considerable development of women’s paid work, especially in clerical and commercial occupations and in the light industries. Women swarmed into shops and offices in the wake of the typewriter and the telephone, but wherever they went they tended to take the bottom place.’

Exodus of female staff before the Great War

In fact, there were some women were working in the Civil Service before the outbreak of the First World War, but only in certain clearly defined areas and with very limited opportunities as regards pay and promotion. In this regard it is interesting to note that at the very beginning of the twentieth century, the Civil Service, which had been for thirty years the leading employer of women clerks, began to see a mass exodus of its best-qualified clerical workers and had problems with recruiting replacements. When in 1907 the Treasury commissioned a study of the problem, businesses were found to be offering both better wages and better opportunities to female staff than the public sector.

A book published in 1913 entitled ‘How to enter the Civil Service’ includes a chapter on women as civil servants. The ‘grades of appointment’ available to women included women clerks, learners and sorters in the Post Office, women officers in labour exchanges, typists and telephonists. More senior and more highly-paid roles as Women Inspectors in the Board of Education and Lady Factory Inspectors are mentioned (‘Special’ roles), but the author warns that these posts are few and rarely available.

Public appeal for women to join the Civil Service

It was only in 1915 that the major influx of women into the Civil Service began. A letter to Government Departments from the Board of Trade dated 22nd April 1915 in National Archives file CO 323/666/50 stated that, ‘a special register is being compiled by the Labour Exchanges of women who, in response to a public appeal issued by the President of the Board [of Trade], have signified their willingness to undertake service during the continuance of the War to release men for combatant duties.’ Over 30,000 women registered in the first few months, and one of the Board of Trade’s stated aims was ‘to supply a large number of Women Clerks qualified to take the places of Officers who may be released for service with the Colours.’ By April 1916 the number of direct replacements of men by women in the Civil Service was 73,000. By December 1918, the number of women and girls employed in the Civil Service and Post Office was estimated at 225,000, of whom eighty per cent were clerks in Government Offices.

Reactions of the existing staff

The arrival of the new temporary women clerks was not greeted with unalloyed joy by the existing staff. In the July 1915 edition of Red Tape, the publication of the Assistant Clerks’ Association, one correspondent suggested that it had not been demonstrated that ‘the supply of unemployed men clerks whose services could have been obtained for a reasonable wage, had been exhausted.’ The second, and possibly more serious concern expressed, was that there had been ‘a good deal of petty patronage in introducing temporary women clerks into the Civil Service.’ For Assistant Clerks, who had been obliged to undergo stringent examinations in a range of subjects to obtain their posts, this was anathema. It appeared to be a return to the system which existed before the reform of recruitment practices arising from the Northcote-Trevelyan Report (1854) and, as a result, it aroused a great deal of suspicion.

The new arrivals were not particularly welcomed by the permanent female staff either. One criticised the “temporary”, who came ‘in all the glory of paint and powder, short skirts, high cloth boots, transparent blouses. She came – men saw – she conquered…. I have heard tell of men, formerly confirmed misogynists, who now sit surrounded by a bevy of beauty and find the official day all too short.’

Attitudes of the time

In addition, rather negative comments were made about the abilities of the new arrivals, with mathematics being regarded as a particular weakness. Some male staff also complained through the columns of Red Tape that they were obliged to provide assistance and training for the new female clerks because of their lack of experience. One regular contributor to the publication wrote a poem on the subject, entitled To A Sweet Substitute. In it he states to his female colleague:

‘Hours I spend your work inspecting,

All your little slips correcting’

Overcoming prejudice

The ‘sweet substitutes’ in due course began to fight back against the complaints. One, in March 1916 wrote of ‘the sacrifices that are made daily by thousands of us, many of whom have given up the pleasures and comforts of home, and make long journeys daily (in my own case over 60 miles) in order to keep posts open for those of our men who must go forth to fight.’ Another woman commented: ‘Does it occur to your correspondent …. that we are making a financial sacrifice by remaining at our posts, taking into consideration the good salaries that are cheerfully paid at the present time in business houses?’

However, in due course there was acceptance and acknowledgement that, ‘the temporary clerks, in spite of the utter lack of discrimination in their selection, have as a body justified themselves. In the mass they are doing useful work and doing it well.’

At the end of the First World War many temporary women clerks were made redundant, although in October 1919 a competitive examination for women clerkships was held and temporary clerks with 6 months approved service were eligible to apply. So this period opened the door to further employment opportunities in the Civil Service for women, although it was a step forward rather than a wholesale change. Nevertheless, women had proved that they were capable of far more than had previously been expected of them. As Ray Strachey commented of women’s work on the Home Front, ‘No one, not even the feminists, had thought that women could be so versatile and so efficient.’

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.