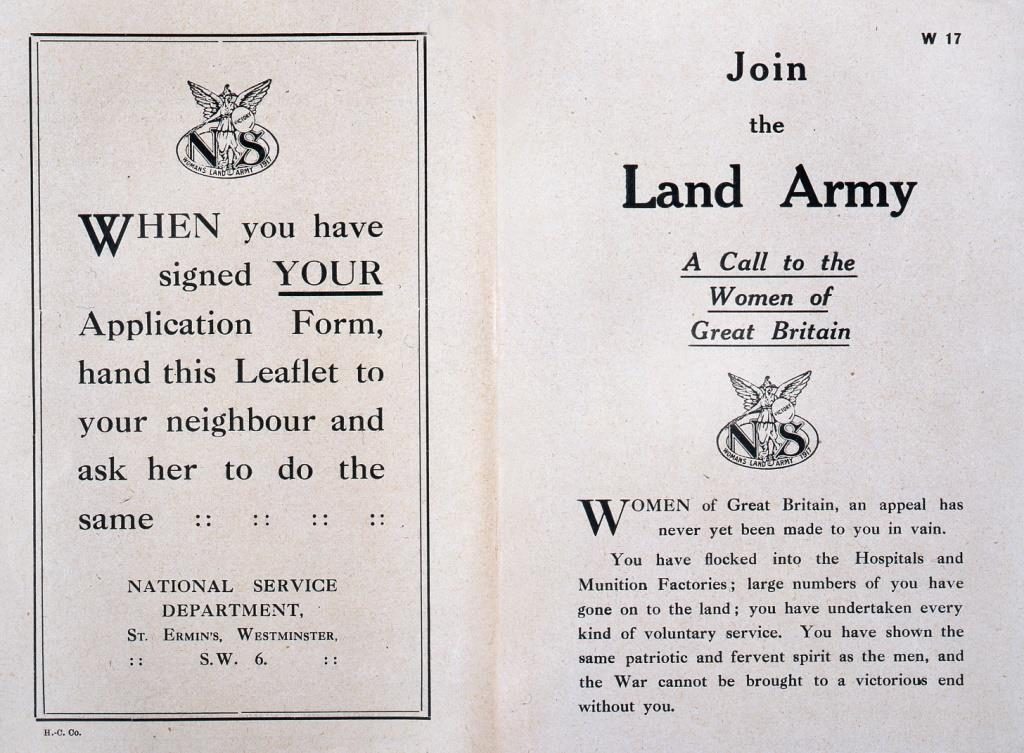

To begin this blog, I am going to set the scene and ask a few hypothetical questions. Imagine it is the height of summer, 1917. The Great War has been raging for almost three years, and there is still no end in sight. In addition to the rising death-toll from the fighting fronts, food shortages on the home front have significantly increased. The Government has issued a series of posters and leaflets asking women to volunteer on the land (see Figure 1). Would you consider joining the Women’s Land Army? Would you be willing to work long hours on a farm to help produce food for the nation? Would you consider it your patriotic duty?

Pre-Women’s Land Army: Women Land Workers, 1915-1916

Over the course of the Great War, thousands of women across Britain took on job roles traditionally assigned to men, as the latter enlisted. In 1916, the passing of the Military Service Act made it compulsory for every British man aged 18 to 41 (amended to 51 in 1918) who was unmarried; a childless widower, or outside of protected employment, to sign up.[1] Women’s work, in areas such as agriculture, became indispensable to replace the increasing labour shortage.

In 1915, under the wartime coalition government of Herbert Henry Asquith, William Palmer, 2nd Earl Selborne, was appointed President of the Board of Agriculture and Fisheries, and charged with overseeing the country’s food supplies.[2] Lord Selborne established the War Agricultural Committees and, with the Board of Trade, Women’s County Agricultural Committees across the counties (the latter were transferred to the sole authority of the Board of Agriculture in late 1916). [3] These committees worked collaboratively to organise women land volunteers. Whilst Lord Selbourne had desired a national campaign to recruit, train and distribute these volunteers, his vision never came to fruition. Something drastic had to be done.

A new beginning: the official formation and organisation of the Women’s Land Army, 1917

David Lloyd George was elected Prime Minister in December 1916, and dedicated to resolving the Food Problem.[4] He appointed Rowland Prothero as President of the Board of Agriculture (Lord Selborne had resigned earlier that year). Prothero subsequently established the Women’s Branch, which was responsible for the WLA, in early January 1917. The Branch subsequently became a division of the Food Production Department in March 1917, and worked with the Women’s Section of the National Service Department (which oversaw recruiting). Miss Meriel Talbot – previously the first Woman Inspector of the Board of Agriculture – was appointed Director of the Women’s Branch.[5] The objective was simple: ‘to procure, train and equip a large number of Women Land Workers able and willing to devote their whole time to agricultural work wherever they are required’.[6] The Women’s Land Army was consequently split into three parts: agriculture (under the Land Army Agricultural Section or ‘L. A. A. S.’, which is my main focus here), forage, and timber, with volunteers able to choose which section they joined (subject to demand).[7]

Publicity, Propaganda and Recruitment

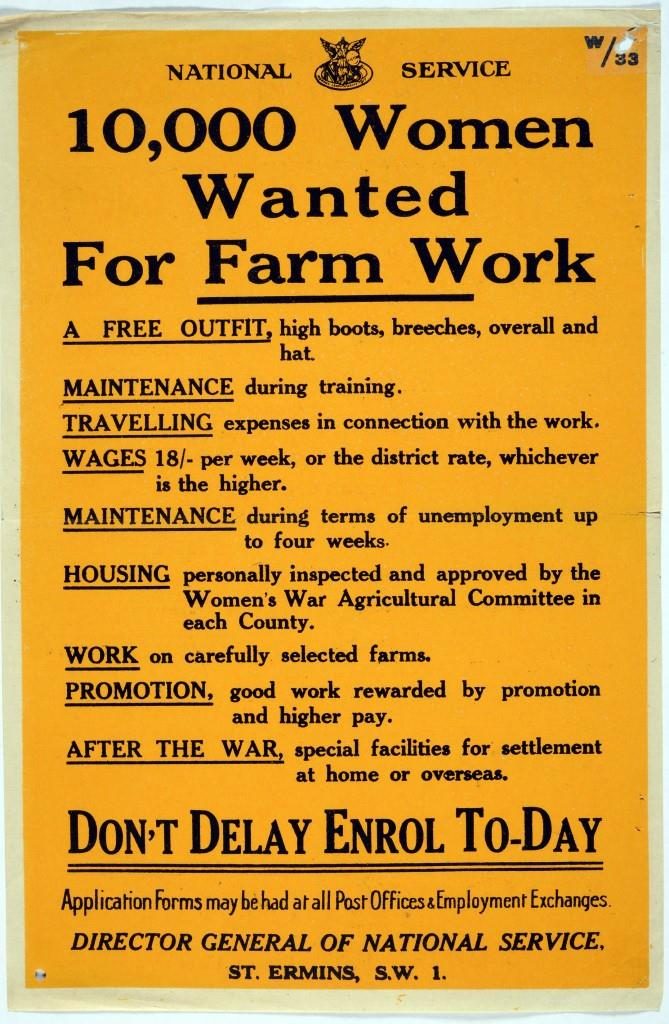

Repeated appeals to ‘women of all classes’ were issued throughout 1917, and considerable publicity campaigns generated.[8] Tapping into military propaganda that sought to enlist soldiers, posters, leaflets and cinematic clips were designed to capture women’s sense of patriotism and self-sacrifice. Condemning the ‘U-Boat Scourge’ for destroying the nation’s imported food supplies, the Government appealed to ‘strong and suitable women’ over the age of 18 (although women under 21 had to obtain consent from their parents/guardians before registering) to ‘come to the Country’s assistance’, and help ‘provide our own [food] supplies in much greater quantity than ever before’.[9] Posters, too, such as Figures 2 and 4, sought to entice women, by advertising the perks of joining the WLA (the wage was increased to 20/- upon completing an efficiency test), and portraying the gruelling work in an idealised, romanticised light.

A Non-Military Organisation

Although called the Women’s “Land Army”, it was not a military organisation. This was because the women were employed by individual, private farmers, and not the State.[10] Nevertheless, Miss Talbot was determined it be a disciplined organisation, reminiscent of the military style.[11] In addition to the training, the women were provided with designated Land Army uniforms and armbands that symbolised their service to the war (Figures 3 and 4); a code of conduct (although this was not uniform across the counties), and faced disciplinary action for misdemeanours.[12] Whilst there was no ranking structure, per se, there were opportunities for promotion, firstly, to Group Leader, and then to Instructor in a Training Centre, complete with higher wages and ‘distinctive armbands’.[13] Awards of merit were also inaugurated: the Good Service Ribbon was issued after six months, and the Distinguished Service Bar for acts of courage and special devotion to duty (awardable only by the Director of the Women’s Branch).[14]

Overcoming obstacles

Joining the WLA, too, was no easy feat. Many of the women had no experience of agricultural work, which was physically demanding. Types of work in the L. A. A. S., for example, included stone picking, manure spreading, vegetable planting, milking, stock tending and rearing, hay making, and ploughing. Volunteers had to pass both an interview and medical examination, and undergo four to six weeks training (dependent on experience) in designated training colleges or on farms upon their acceptance. They had to be prepared to work anywhere for the war’s duration (this was later amended to either a 6 or 12-month commitment). They also had to overcome the conservativism of farmers who were often reluctant to accept female hands, although this did change with the organisation of public demonstrations and popularisation of women’s agricultural work across the country. In light of this, whilst thousands of women registered for the WLA, the tough selection process resulted in considerably lower numbers of women actually working the land.[15]

The War's End: Demobilisation of the WLA, 1919

The WLA was not a seamless creation, and faced numerous contradictions, tensions, and issues, particularly in terms of its organisation, over the course of the war. Nevertheless, it continued its vital work throughout 1918 and 1919 as the food situation in Britain, and the number of men who would return to agriculture post-armistice, remained uncertain. It was eventually demobilised (not disbanded) in late 1919. Although the Women’s Land Army constituted only a small part of the agricultural labour force, some 27,000 women in England and Wales answered the Government’s call, thereby contributing an invaluable service to King and Country. [16]

Footnotes

-

- The National Archives (TNA) MH 47/142/1

- Bonnie White, The Women’s Land Army in First World War Britain (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), p. 12.

- TNA: MAF 59/1.

- Gillian Clarke, The Women’s Land Army: A Portrait (Bristol: Sansom & Company Ltd, 2008), p. 19.

- Clarke, p.20

- TNA: NATS 1/1275. The Women’s Branch actually dealt with all women’s employment. The agricultural section constituted only one part of its repertoire.

- TNA:MAF 42/8

- TNA: MAF 42/8; TNA: MAF 59/1.

- TNA: NATS 1/1308

- TNA: MAF 42/8

- TNA: MAF 59/1

- TNA: MAF 42/8

- TNA: NATS 1/319

- Clarke, p.36.

- TNA: MAF 59/1; TNA:MAF 42/8

- White, p.8

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.