100 years ago this day saw the execution of one of the most daring amphibious raids of the First World War, in an attempt to stop German U-boats from attacking British ships. German submarines posed a constant threat to British vessels in the Channel. Throughout the war, they sank a third of Allied merchant shipping. This led to food rationing in order to deal with the low supplies. According to Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, Britain needed to neutralise the threat from U-Boats based at Zeebrugge and Ostend ports to stay in the war.

Zeebrugge Harbour and Canal

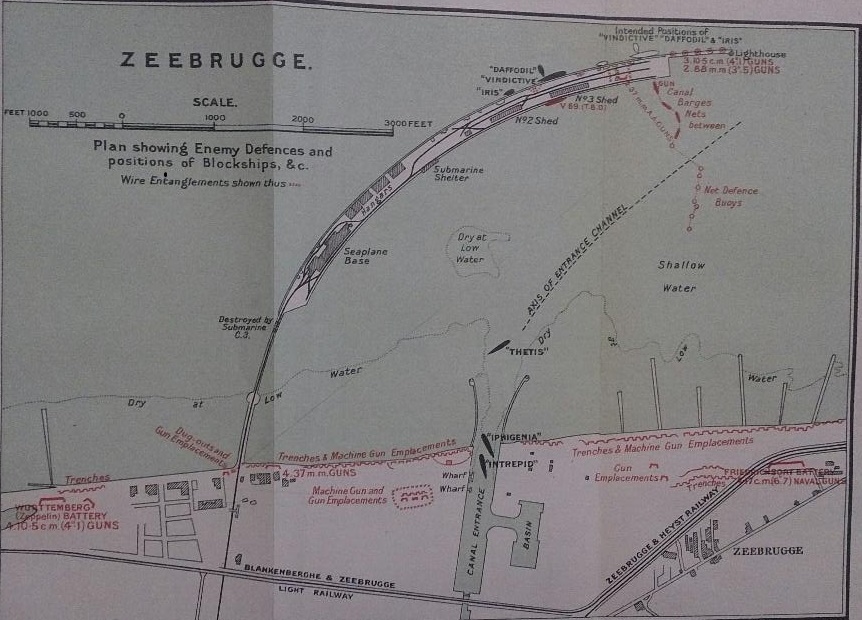

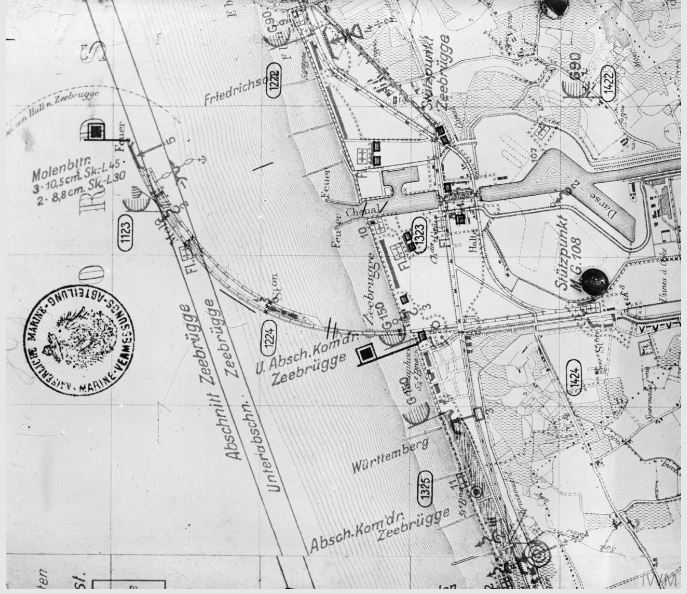

The Germans had held the ports of Zeebrugge and Ostend since 1914. The ship canal from Zeebrugge gave access to the inland port of Bruges and offered the perfect hiding place for submarines, torpedo boat destroyers and other vessels. The canal provided close access to the English Channel and the North Sea. However, the threat from U-boats was not only from direct assaults, but also from the mines they laid.

The strategic importance of Zeebrugge meant that the Germans had strong defences along the coast. Their most powerful coastal guns could reach more than 20 miles out to sea. To add to British problems, the entrance to the harbour at Zeebrugge (protected by a breakwater known as the Mole) was heavily defended by mines.

The plan of attack

A plan to block Zeebrugge and Ostend was developed by Vice-Admiral Sir Roger Keyes, picking up on previous planning by his predecessor, Admiral Sir Reginald Bacon, in his role in command of the Dover Patrol. This had three aims:

- to block the ship-canal entrance at Zeebrugge by sinking ships across it (known as blockships)

- to inflict maximum damage on both ports

- to block the entrance to the harbour at Ostend

The plan required precision and an unobserved approach through mine-strewn waters. Weather conditions had to be right in terms of wind and tide. The sea had to be reasonably calm as the navy was using three old cruisers packed with concrete as blockships. Navigation would be difficult because the waters were shallow in some places, and the sands shifted and the attack would take place at night. There were also submarine nets across the harbour.

To get the blockships and the motor launches into the harbour past the Mole required a diversion. This would be provided by a smokescreen, developed by Frank Brock, of the well-known fireworks family. He would also participate in the raid. HMS Vindictive would pull alongside the Mole and land storming parties. Their role was to engage the German marines defending the harbour and knock out the gun batteries on the Mole. Motor launches would rescue the crews of the blockships and the submarines before returning to Britain.

An unsuccessful attempt to carry out the operation was made on 2 April, when the attacking force was recalled due to adverse wind conditions.

23 April

The flotilla of 76 ships, carrying 1,700 men was led by HMS Vindictive. This included two Mersey ferries, Iris and Daffodil, to transport the marines onto the Mole.

Just after midnight on 23 April they arrived at the harbour. At the last moment the favourable wind which had supported the smokescreen changed. The shore batteries observed the approach and fired on HMS Vindictive. As a consequence, Vindictive pulled in further from the landward end of the Mole than planned and had to be nudged against the Mole by one of the ferries, Daffodil. It was difficult for the men to disembark because the ship was under fire and the angle between the ship and the Mole was steeper than expected. Vindictive remained alongside the Mole under heavy fire for an hour, before re-embarking the survivors of the fierce fighting ashore and returning to Dover.

One of the blockships, HMS Thetis, did not reach the canal entrance, but grounded on a sandbar and sank in the outer harbour. The other two, HMS Iphigenia and HMS Intrepid were scuttled across the entrance to the canal. The British submarine C3 managed to sail under the viaduct and blow it up, breaking the connection of the Mole to the land. This prevented German troops from reinforcing the Mole.

The result

At the time, the British press claimed the Zeebrugge raid as a success. The German press argued it was a German success because the Mole had been defended. The canal entrance was blocked, but within a few days the Germans were able to clear and dredge a channel for submarines to leave during high tide.

The offensive provided a boost to British morale although the claims for its success has subsequently declined as the closures were only temporary. No such claims were made for Ostend, where both blockships ran aground before reaching the harbour entrance.

British casualty figures varied, but around 200 men were killed, 400 wounded and a small number taken prisoner. The Germans lost twenty-four men.

The bravery of the men involved, however, is undoubted. Eight Victoria Crosses were awarded for the Zeebrugge raid, and three for a later raid at Ostend.

The two Mersey ferries were granted permission by the King to prefix their names with ‘Royal’. In 1919 they returned to their duties carrying civilians.

Further reading

London Gazette Despatches https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/31189/supplement/251

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.