The British Embassy Bangkok is truly one of the most spectacular British properties overseas. The 43,922 square metres of land accommodates the Ambassador’s residence, 2 monuments, offices, staff living quarters, tennis courts, a swimming pool, greenery and a private pond. In the heart of Thailand’s luxury retail district, it contrasts with other tall structures. It is a symbol of soft power from the colonial era in the midst of the modern day quest for economic development.

In January 2018, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) announced its sale for £420 million, the biggest land deal ever for the FCO up to the time of this publication. This year the Embassy will relocate to a modern office space, in the same fashion as many of its foreign counterparts whose governments also decided that it is the right time to realise their return on investments.

But before we move on to the future of shiny furnishings and newly painted walls, we look back at the (soon to be) old British Embassy Bangkok and its remnants of the past.

From the river bank

The cornerstone of the first British consulate in Siam lies in the success of the Bowring mission to Bangkok in March 1855. It was at the bank of Chaophraya River where Sir John Bowring alighted from the Rattler, and it was by this river that the first British consulate was constructed one year later. The Treaty which followed his brief visit specified many trade related arrangements, such as conditions in which British subjects can rent and own land and trade in all ports with 3% import duty, as well as terms on extraterritoriality for British subjects. 1

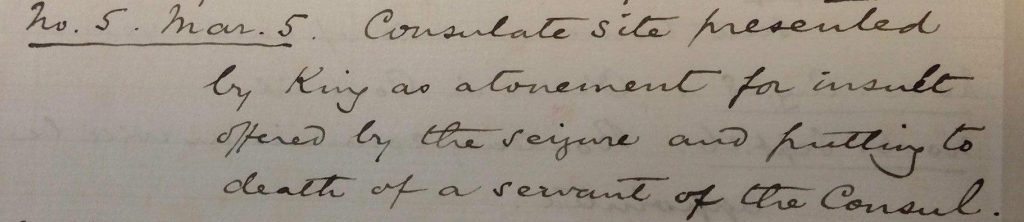

According to the memoirs of Sir Ernest Mason Satow, the Minister Resident and Consul General to the Kingdom of Siam from 1885 to 1889, the site of first British consulate in Bangrak district was given to Her late Majesty’s Government as ‘atonement for insult’ after a staff member of the consulate was beaten to death.

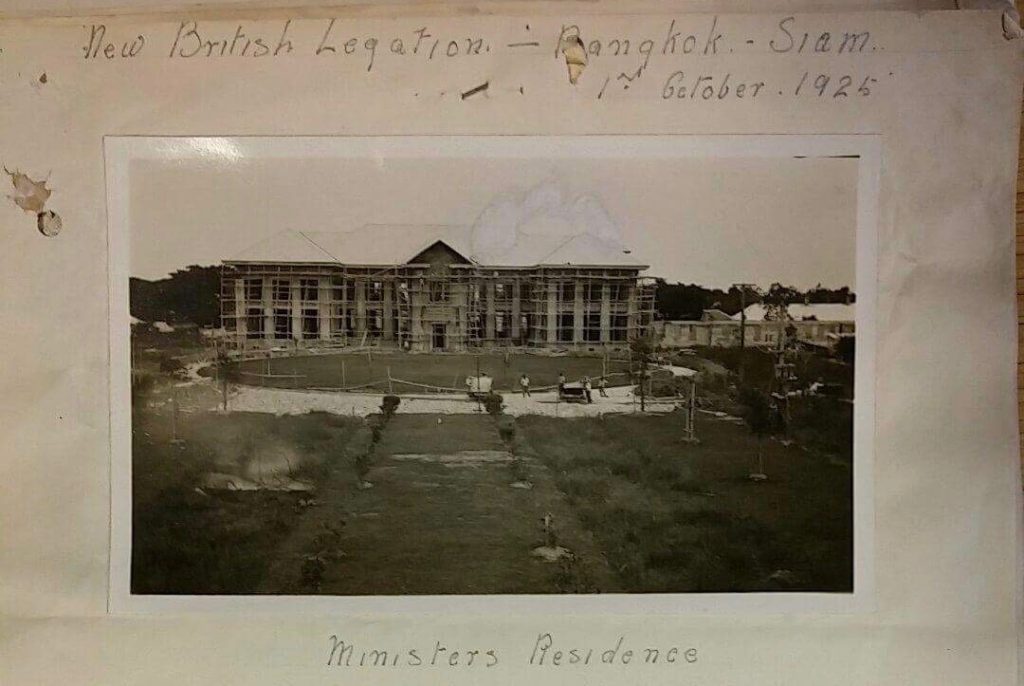

The consulate status was raised to a legation in 1895. In 1925, the legation moved to the current site in Ploenjit, just under 4 miles from Bangrak district. The building cost of 1,058,000 Ticals (approximately £61,7602) plus 40,000 Ticals (£2,335) for the acquisition of a pond was partly met by the proceeds from the sale of the old site by the river.

To her late lamented Majesty Queen Victoria

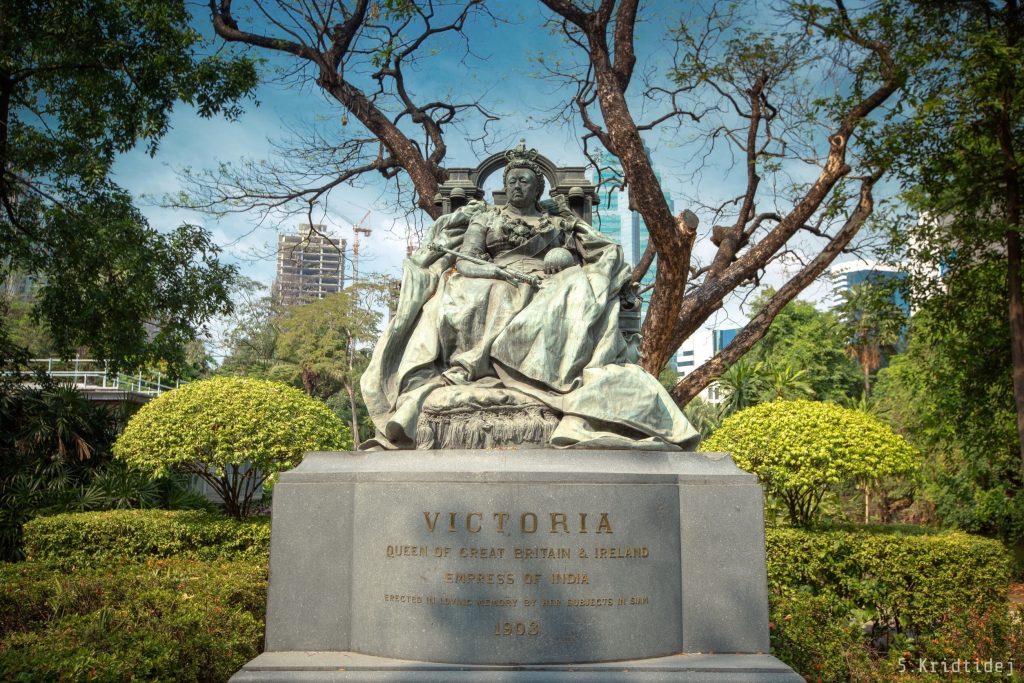

The British subjects in Siam had an important role in shaping an initiative which became an object of great admiration until this day. In August 1901, they raised a sum of 21,838 Ticals (approximately £1,275), mainly from Chinese-British subjects, to erect a memorial to Her Late Majesty Queen Victoria3. When William J Archer, the Counsellor of Legation, wrote to inform the Marquess of Lansdowne of this proposal, he also included his views that “permission should be given to erect the memorial in the Legation grounds, for the reason that no other fitting place can be found in Bangkok.”

The bronze statue is 14 feet high, 30 feet at its widest point, and weighs around 2 tonnes. It is the work of Sir Alfred Gilbert, the sculptor of the Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain in Piccadilly Circus.

The monument is a reproduction of the one in Winchester Castle. There are 3 statues cast from the same mould, another is in Newcastle. In May 1903, the Times reprinted a report from the Bangkok Times, about the unveiling ceremony which took place at 5:15pm on 23 March 1903: "The Crown Prince [Vajiravudh] then drew the cord, everyone rose, the officers present in uniform saluted, the civilians uncovered, and the flag slipped aside, revealing the bronze statue of the Queen, represented as seated upon a throne, crowned, bearing sceptre and orb, and arrayed in the robes of State".

Later in 1962, Edward Muir, a British Diplomat, documented a local story about the memorial during the Second World War. When Siam4 acceded to Japanese demands for passage through the country to invade Burma and Malaya in December 1941, it was said that the Japanese 'bricked this statue in but left a slit opposite Queen Victoria’s eyes so that she could see out'.

WWI memorial and environmental consideration

Back in June 1919, the British community in Siam also proposed to erect another memorial, this time to honour of the British subjects from Siam who had fallen in the war. Correspondence in the archive suggests that great care was taken to minimise the environmental impact.

Sir Herbert Dering, His late Majesty’s Ambassador to Siam, wrote in his memorandum to the Foreign Office, “The memorial is planned to stand exactly opposite a very fine old tree (known as the Sacred Bô tree) of which the roots are wide spreading. … Any disturbance of its roots is in every way undesirable, and would probably bring about its fall. The memorial would require a certain depth of foundation; and I should view with distaste any interference with the vitality of the great tree”.

Both monuments were later moved following the relocation of the embassy in 1926. Today, they stand amid the spreading branches of charming old trees in the embassy compound.

‘Spacious, and dignified and beautifully laid out’

Another notable feature of the current embassy compound worth mentioning is the pond. Acquired from Nai Lert about 10 months after the main building contract was finalised, it includes 5,080 square metres of water and 2,480 square metres of land.

On 12 November 1925, Mr A Scots, the legation official noted that “The Pond is offered for T40,000, and while this far exceeds its market value, the value of our property would, I think, be increased by a greater amount by the inclusion of the pond, apart altogether from the abolition of the intolerable nuisance of the noisy Sunday crowds.”

Almost a century later, the valuation of the compound at £420 million proved his judgement outstanding in every respect.

From lamp posts, to a pavilion for the locals to wait in, evidence suggests that great efforts were made towards the design of this spectacular property. Upon inspection in July 1962, Edward Muir wrote that he was “very glad indeed to have seen this compound, which I have always understood was one of our most successful and agreeable efforts. So it is. It is spacious, and dignified and beautifully laid out. The main house, which I suppose was about the last large house we built in the Far East in the old spacious style, is extremely comfortable and well furnished.”

However, such an impressive property comes with great maintenance costs. When Muir noted that the offices in the adjacent buildings were in disrepair, he recommended that “we ought not to spend any more money on patching this deplorable mess and that a scheme should be worked out for entirely rehashing the offices”. Interestingly, a similar opinion re-emerged five decades later when Boris Johnson, then Foreign Secretary, said that he was “determined to ensure that our diplomats have all the necessary tools to do their job effectively. This includes working in modern, safe, fit-for-purpose premises not just in Bangkok but around the world.”5

The proceeds from the sale of the compound will be used to relocate the British Embassy in Bangkok this year and improve other British Embassies around the world. Another milestone in British diplomatic endeavour, as we invest in the future while honouring our heritage through reminiscence.

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.