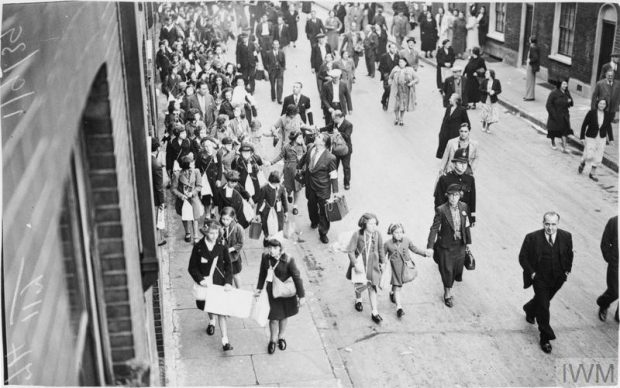

Photographs of the evacuation of British children in 1939, excitedly waving from packed trains or with name tags round their necks, have become some of the most emblematic images of the Second World War. The children’s forced move represented the nature of total war, a conflict that involved even the youngest members of British society.

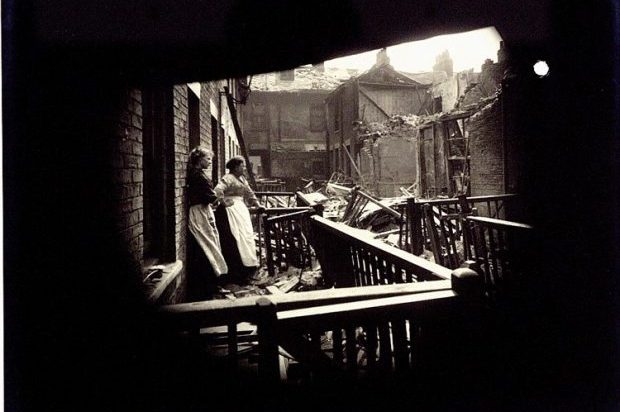

But the origins of childhood evacuation in fact lie much further back. It was in the early twentieth century that governments and populations across Europe first began to speculate on the dangers of aerial bombardment. H.G. Wells’ 1907 novel 'War in the Air' predicted the growing threat of attack from the air and governments worried how cities and urban crowds in particular would respond. The First World War saw some of these fears realised: although often forgotten in popular memory, British cities were bombed by zeppelins throughout the 1914-1918 conflict, resulting in the deaths of 1,239 civilians, half of whom were women and children.

Interwar Developments

After the First World War, there was therefore heightened interest in how to defend the ‘home front’. In 1924, the influential Committee of Imperial Defence (CID) formed a sub-committee on civil defence, the Committee on Air Raids Precaution, led by Sir John Anderson (whose name was later associated with air-raid shelters). Their task was to consider practical responses that could preserve human life during air attacks, from gas masks to underground shelters. In 1931, the ARP Committee appointed its own sub-committee on evacuation, another possible preventative measure, led by Sir Charles Hipwood. Much of its early attention centred on London, on the timing of a successful evacuation and on how to ensure the effective maintenance of crucial infrastructure if people were evacuated. Committee members also noted that any evacuation should be voluntary rather than enforced, as the latter might cause even more problems and panic in a wartime situation.

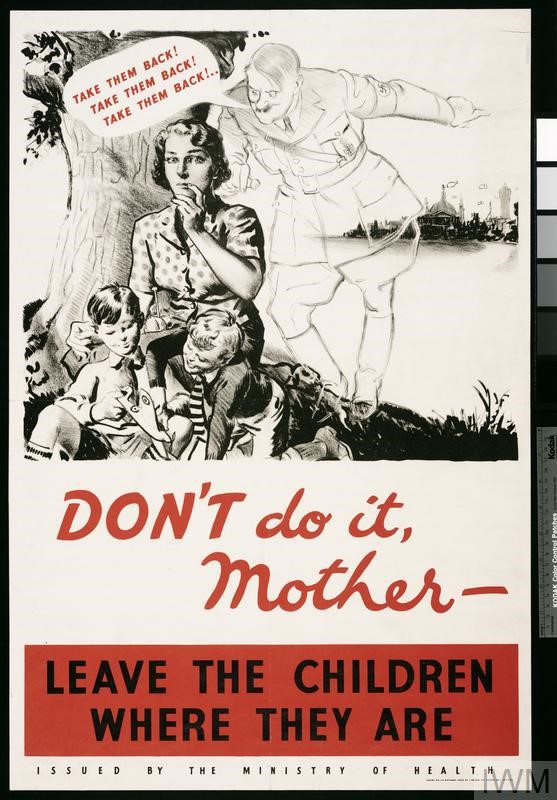

As the threat of war in Europe loomed by the late 1930s, the Anderson Committee published a report on evacuation in July 1938, which prioritised schoolchildren and mothers with infants. It was deemed better value for these evacuees to be billeted in private homes in safer, ‘reception’ areas of the country, rather than building special camps. Hosts in these areas could face a fine if they refused to take an evacuee. Railway staff, local police and teachers all helped to shape these plans, which were largely ready by the summer of 1939.

On the 3 September 1939, Britain and France declared war on Nazi Germany. Two days’ earlier, on 1 September, the government had initiated Operation Pied Piper, which would see the evacuation of over 1.5 million people from urban 'target' areas, of whom 800,000 were children. Contrary to popular memory, these evacuees did not just come from London or England, but from cities like Manchester, Birmingham and Glasgow too.

‘The Louse is Not a Political Creature’

The experiences of children in reception areas, which were mostly rural communities, were varied and have been subject to much debate among historians. For some, living in a rural setting was an unparalleled adventure, which was enjoyed and remembered fondly; they met people with whom they retained contact for the rest of their lives. Others suffered at the hands of cruel or indifferent hosts. For the hosts, some were appalled at the children’s health and personal hygiene. Lice and enuresis (bed-wetting) were seen by some as symptoms of neglect, poor mothering and even ‘problem families’ in working-class communities. But as Richard Titmuss, the official historian of the wartime social services argued, the ‘louse is not a political creature’ and the apparent infestation of urban children might well have originated in the evacuation taking place during the school holidays and aggravated by travelling conditions, rather than just due to societal factors. Bed wetting also might have originated in the psychological shock of moving. Prejudice might have played a role in the circulation of these stories, which were sometimes exaggerated by the popular press.

Many children did not remain long in reception areas. By January 1940, around 900,000 evacuees had returned to target areas, despite government calls to 'leave the children where they are'.

Subsequent waves of evacuation followed: 1.25 million people left cities during the Blitz in 1940 and another wave left during the 1944 V1 and V2 rocket attacks. Not all evacuations were to protect from aerial bombardment though: the children of working or expectant mothers, whose husbands were away with the Services, were sometimes evacuated too.

Other children travelled far further than rural reception areas. Before 1940 about 11,000 children were privately funded to travel overseas, many to the United States. Between July and September 1940, a further 3000 were sponsored by the government to travel to the Dominions, particularly to Canada, Australia and New Zealand, before the risk from torpedo attack at sea was deemed too great. This comparatively short-lived and voluntary scheme was one of many twentieth-century child migration schemes. Some were voluntary, others enforced, and aimed to give children a 'better life': many are now the subject of ongoing inquiries into cruelty, abuse and neglect.

Did Evacuation lead to the Post-War Welfare State?

On the one hand, the evacuations of the Second World War led to greater state involvement in the lives of families, which led to changes in the administration of social services, the School Medical Service and the provision of nursery schools. It also led to an increased interest in childhood mental health: psychoanalysts such as Anna Freud (daughter of Sigmund) worked with evacuee children and developed theories on the effects of mother-child separation. Many argued that the future stability of the very state itself rested on the growth of well-adjusted children. Evacuation also exposed disparities in wealth and health which encouraged people to look for solutions in a comprehensive welfare system, something that Clement Attlee's Labour Party seemed to promise with its 1945 general election manifesto.

Yet on the other hand, evacuation potentially also deepened class antagonism and prejudices. Others would argue that many of the post-war changes in welfare originated far earlier, in the aftermath of the First World War or even the Liberal Reforms of the 1910s. Some civil servants felt evacuation had exposed the need for greater efforts in universal education, rather than improving welfare, housing and health. The legacy of evacuation thus remains a point of contention.

Nor did evacuation stop at the end of the Second World War. In an uncertain post-war world, increasingly caught up in Cold War struggles, British civilians were evacuated across the world: from India in the run-up to independence and in Palestine in 1947 under 'Operation Polly' at the end of the British Mandate. Plans even existed to evacuate British families from the increasingly large military base communities scattered across Germany if the Russians invaded. Today, the British government continues to devise evacuation plans for non-combatants, particularly in the world's most politically volatile regions.

The long history of evacuation still continues.

Keep tabs on the past. Sign up for our email alerts.