The principles set out in the Atlantic Charter eighty years ago remain key to the global vision shared by the UK and US. But its terms also contained the roots of international tensions that persist today: for example in relation to Britain’s imperial legacy, Russian suspicions of Western intentions and transatlantic differences over trade.

‘Meaningless platitudes and dangerous ambiguities’?

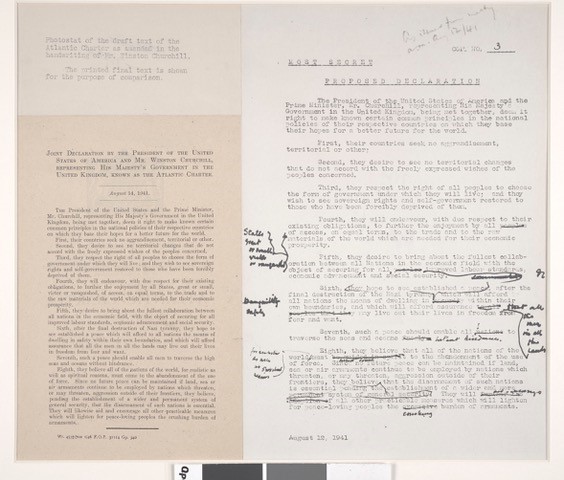

The Charter set out 8 principles: today they may seem uncontentious, but in 1941 some were difficult for Churchill to accept. He had no problem with saying that the US and US sought ‘no aggrandizement’, or with expressing hopes for world peace and disarmament. But stating that the two countries desired ‘no territorial changes that do not accord with the freely expressed wishes of the peoples concerned’, and respected ‘the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live’ was clearly a threat to the British Empire, as Roosevelt intended.

The fourth principle - that they would endeavour to ‘further the enjoyment of all states, great of small, victor or vanquished, of access, on equal terms, to the trade and to the raw materials of the world which are needed for their economic prosperity’ - was rooted in US determination to dismantle Imperial Preference and free up world trade to American advantage. In August 1941, however, the prize of a public linking of British war aims with US aspirations outweighed these concerns for Churchill.

Face-to-face diplomacy at a dark hour for Britain

Churchill and Roosevelt already had good relations. The President had extended a good deal of help to a Britain reeling from the Battle of Britain, the Blitz, shortages and military setbacks. But both men enjoyed the grand gesture of a wartime shipboard encounter and understood the importance of strengthening their personal bond. Churchill had been given permission to leave the country by King and Cabinet, and faced a potentially hazardous voyage across the Atlantic (although he, unlike Roosevelt, knew the cracking at Bletchley Park of German naval Enigma meant instructions to U-Boats could be intercepted). The disabled Roosevelt found moving around on ships challenging, and saw the Conference as an opportunity to demonstrate his own courage and determination while assessing Churchill’s.

All measures short of war

Such decisions did not require the President and Prime Minister to meet personally. There is some truth in the criticism that the conference, and the Atlantic Charter, embodied more symbolism than substance. But that symbolism was important in forging a close, and valuable relationship between Roosevelt and Churchill for the rest of the war. It also acted as a useful counter to American anti-interventionists who argued that Britain was just trying to drag the US into another conflict. And it laid the foundations for an Anglo-American partnership that remains at the heart of British foreign policy.

The Atlantic Charter, even though its terms contained the seeds of controversy and international tensions, expressed important principles and signposted issues that continue to face governments worldwide. A copy of it still hangs on the wall in the office of the Permanent Under-Secretary of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Its terms remain worthy of scrutiny.

The text of the Atlantic Charter is online: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/wwii/atlantic.asp

Further Reading

Martin Gilbert, Finest Hour: Winston S. Churchill 1939-1941 (London: Heinemann, 1983)

David Reynolds, ‘The Atlantic “Flop”: British Foreign Policy and the Churchill-Roosevelt Meeting of August 1941’, in Douglas Brinkley and David R. Face-Crowther (eds), The Atlantic Charter (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1994)

Frank Costigliola, Roosevelt’s Lost Alliances: How Personal Politics Helped Start the Cold War (Princeton University Press, 2013)

Peter Ricketts, Hard Choices: What Britain Does Next (Atlantic Books, 2021)

Keep tabs on the past: sign up for our email alerts Follow our FCDO Historians on Twitter @FCDOHistorians

3 comments

Comment by George Peden posted on

Very clear account of an important step in the development of the Anglo-American special relationship.

Comment by Patrocina un niño posted on

Somos una organización humanitaria global, trabajamos para que los niños vivan libres de pobreza, protegidos y en comunidades sustentables. ... ABCW

Comment by zafar hussain posted on

This one is good. Keep up the good work I also visit here: and I get lot of information.