The most that we can say is that we have made the best of a bad bargain, not that we have got a fair deal (Prime Minister Edward Heath, 1 September 1971)

Fifty years ago, Ambassadors representing the 4 Occupying Powers in Germany—France, the UK, US and USSR—signed an agreement on Berlin. This included documents concerning access, communications, and the respective positions of the FRG (West Germany) and GDR (East Germany) in relation to Berlin. Though neither West nor East achieved all they wanted from the negotiations, the fact the agreement was signed at all was surprising to many involved.

The divided city of Berlin had been, since 1945, the fault line of the Cold War. The erection of the Wall in 1961 gave concrete form to ideological, political and military competition between East and West. Berlin problems were a useful stick with which to beat the other side, and until the late 1960s any constructive deal seemed remote. The West resisted recognition of the GDR (East Germany), while the Soviet Union complained about FRG (West German) activities. Meanwhile, Berliners and occupying authorities alike faced daily problems in communications, access by road or air, local government, movement of goods. The agreements reached in September 1971 were intended to address some of these difficulties.

The Cold War context

While Cold War politics made agreement difficult, they also paved the way for the Quadripartite Agreement. The Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 produced a severe East-West chill, but as always after a shock a resetting of relations was necessary on both sides, for economic and geopolitical reasons. From the Soviet perspective, better access to Western (particularly West German) markets and technology was important for economic progress. From a Western viewpoint, constructive Soviet engagement in global issues such as arms control, the Arab/Israeli conflict and the increasing power of Communist China was desirable if it could be achieved without conceding too much ground.

Westpolitik and Ostpolitik

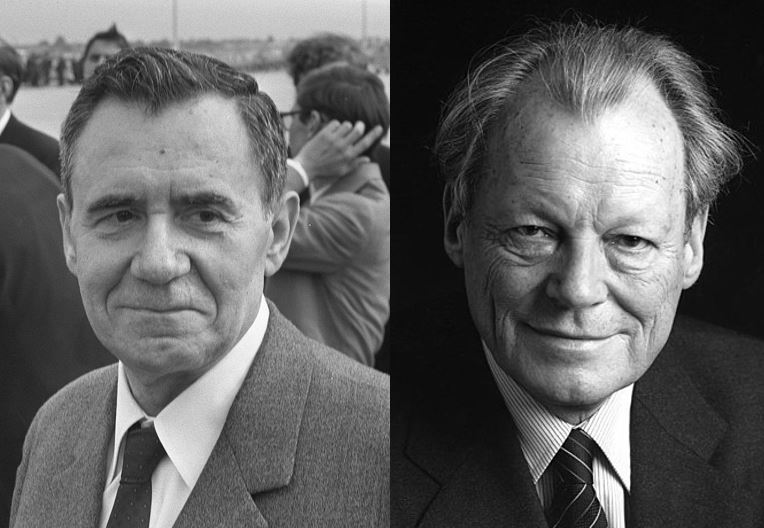

In July 1969 a speech by Soviet Foreign Minister Gromyko indicated a new openness to negotiations on Berlin, and on European security as a whole, with proposals for a security conference. This was Soviet Westpolitik. Meanwhile Chancellor Willy Brandt of the FRG pursued a policy of Ostpolitik, seeing advantage in changing the destructive dynamic of existing inner-German and Soviet-German relations. In August 1970, the USSR and FRG initialled a treaty agreeing not to use force in any matters affecting European security, and to respect the integrity of European states within their current frontiers. The FRG, however, said it would only ratify the Treaty if Four-Power talks on Berlin reached a successful conclusion.

The US and UK governments appeared uncertain how to respond to these developments. In the Foreign Office a good deal of time was spent analysing possible reasons for Soviet willingness to negotiate, revealing considerable disagreement between London and the Embassy in Moscow. Quadripartite talks on Berlin continued, the Russians proving typically tough interlocutors.

In the early months of 1971 briefing for Foreign Secretary Douglas-Home insisted Soviet proposals on Berlin were a ‘deliberate attempt to erode the Western position’ and that Allied authority must be maintained. By June, Western insistence that the idea of a European security conference was a non-starter without an acceptable Berlin agreement appeared to produce stalemate.

‘One final heave might bring the negotiations to a conclusion’

By August 1971, however, both East and West had clearly decided, for a complex set of reasons, that agreement was desirable. The context was the broader interest of improving Western security, Mutual and Balanced Force Requirements (MBFR) talks, Middle Eastern negotiations and Sino-American relations. In the Berlin talks, US and Soviet Ambassadors forced the pace, and a draft text was agreed by 18 August. The Foreign Office felt the agreement met the essential requirements of the Western allies, although enhancing the status of the GDR and recognising tacitly that the Berlin Wall was here to stay. Douglas-Home called it ‘a fair bargain’; the Prime Minister disagreed, though accepting its signature ‘may well be right on the basis that we are prepared to recognise realities’. It might also improve the political atmosphere, paving the way for what would in 1973 become the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE).

‘I decided Mr Gromyko’s time was up’ (Sir A. Douglas-Home)

The conclusion of the Quadripartite Berlin Agreement cleared the way for decisive action against Soviet espionage in the UK: Operation FOOT. Protests against ‘unacceptable activities’ had been ignored or rejected by the Soviet authorities since 1969. Plans for a bold British response were laid in 1971, but the Foreign Secretary waited until the Berlin Agreement was signed before recommending action to the Prime Minister. There was, Douglas-Home said, no satisfactory alternative, and ‘there were strong political grounds for putting an end to this obstacle to a fundamental improvement in British/Soviet relations’. On 24 September 1971, the Soviet Chargé in London was given the names of 105 Soviet officials who were to be expelled, or who if out of the country would not be allowed to return. Here was another Cold War shock: but again, it would not be long before normal business was resumed.

Suggestions for further reading

- Documents relating to the Quadripartite Agreement signed at Berlin on 3 September 1971 are printed in Cmnd 6201 of 1971.

- British policy towards West/Ostpolitik, the Berlin negotiations and Operation FOOT is documented in Documents on British Policy Overseas, Series III, Vol. I: Britain and the Soviet Union 1968-72 (The Stationery Office, 1997)

- Gill Bennett, Six Moments of Crisis: Inside British Foreign Policy (OUP, 2013), Chapter 5: ‘Challenging the KGB’.