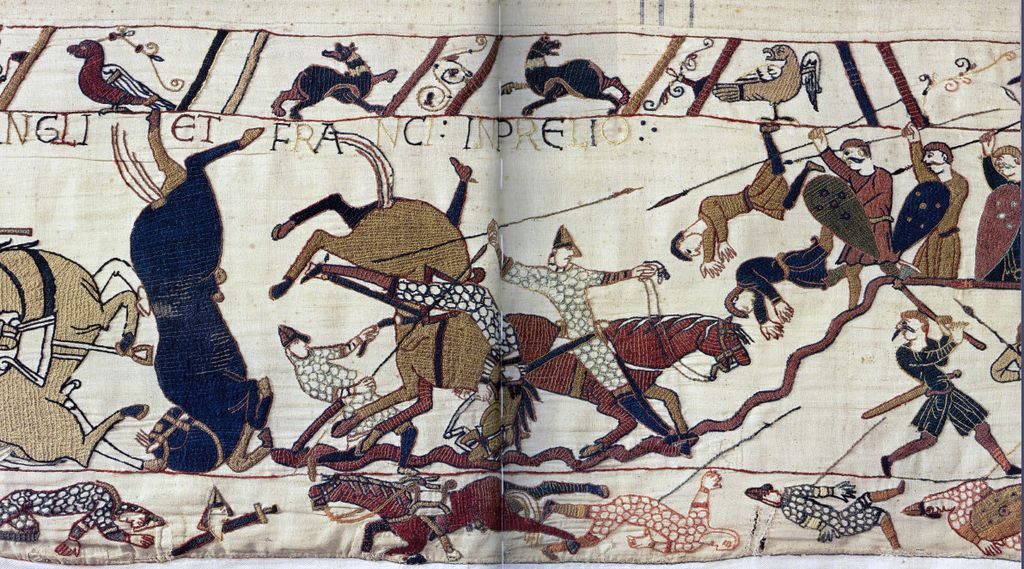

It is approaching 950 years since William the Conqueror triumphed at the battle of Hastings on 14th October 1066; a pivotal date in England's history. Many know the drama that unfolded in what could be described as a real life historic ‘game of thrones’ played out over the course of the year 1066. The main characters Duke William of Normandy, Harold Godwinson and the Norse Viking leader Harold Hardrada, who were all portrayed as protagonists and antagonists in the story depending on which chronicler you read, vied for the prize of the English throne in a showdown of violent conflict. The year 1066 and the battle of Hastings changed the course of English and British history forever and the importance of commemorating this monumental battle has not diminished since.

However plans to commemorate such a famous episode in the history of England could encounter surprising problems, as officials at the Foreign Office discovered 50 years ago when preparations were under way to celebrate the ninth centenary of the battle in 1966.

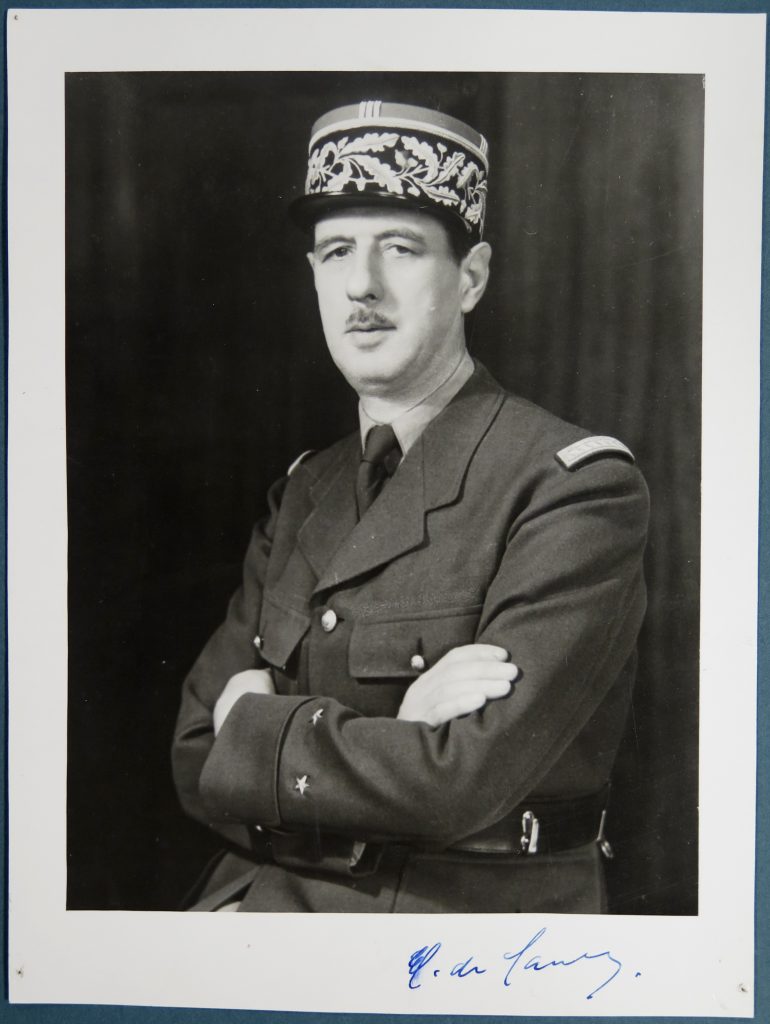

A committee to co-ordinate activities by local authorities and organisations involved in commemorating the 900th anniversary had been established chaired by General Sir Reginald Denning. In an enthusiastic gesture to mark the important anniversary, the committee had suggested inviting the incumbent French president Charles de Gaulle to commemoration events taking place in Britain.

Whilst this was only a proposal it prompted a flurry of correspondence between mildly flustered Foreign Office officials and with the British ambassador in Paris, concerned with the political implications that such a visit would generate.

Concerns arose over the sensitive relationship and attitudes of De Gaulle towards NATO and the European Economic Community. The French president was gradually disentangling France from the NATO alliance and by the end of 1965 France had pulled out of SEATO (South East Asian Treaty Organisation) and refused to participate in future NATO military manoeuvres. He also remained opposed to British membership of the EEC, seeing Britain as too close in its ties with America.

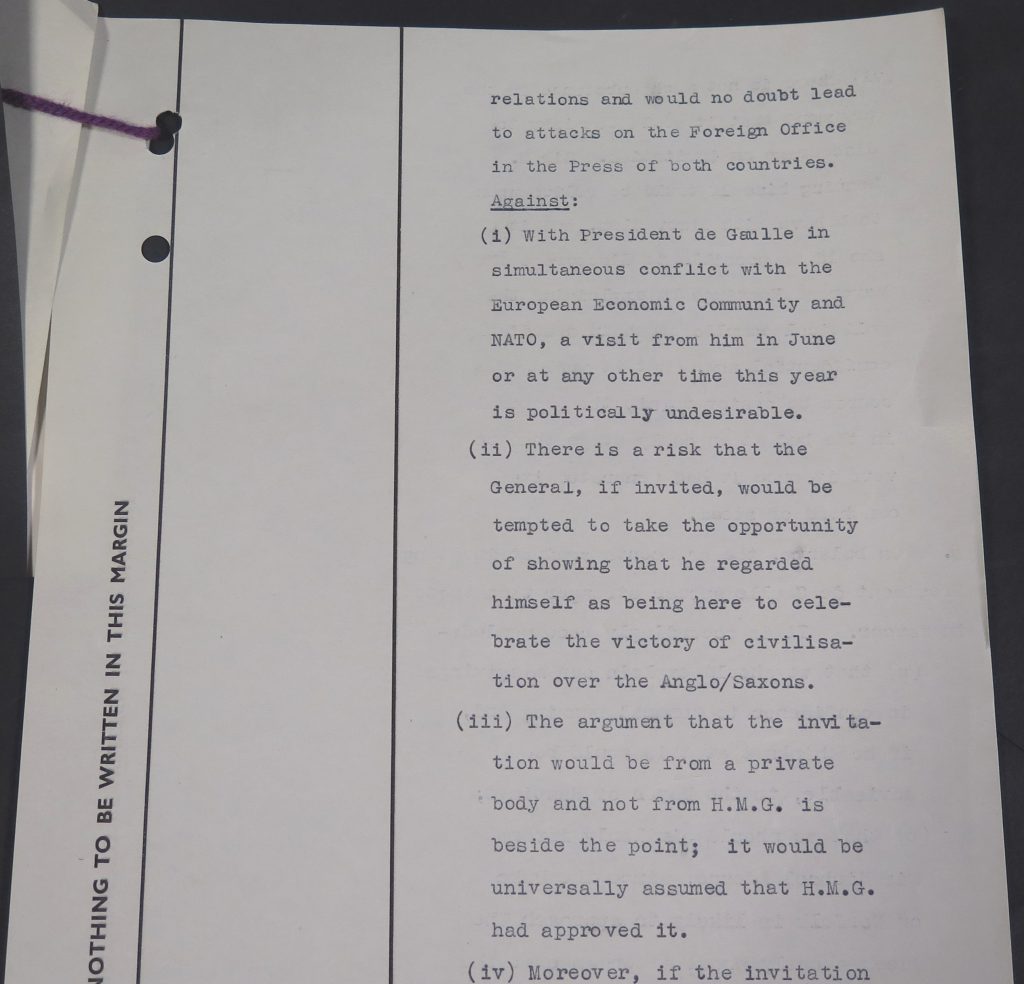

In a minute by private secretary John Nicholls found in FO 924/1629, the arguments for and against inviting the French president were outlined to Foreign Office officials and the British ambassador in Paris.

Arguments for extending an invitation to the president included the opportunity to strengthen Anglo-French relations as expressed by Prince Jean de Broglie, chairman of the French commemoration events for the 1066 anniversary. However the minute went on to raise several stronger objections against inviting de Gaulle to commemorative festivities in Britain. Given the current political climate with contention over the European Economic Community and NATO, a visit would be “politically undesirable” at this time.

There was even disquiet that de Gaulle would to use the occasion for some old fashioned British bashing. Point 2 in the arguments against de Gaulle’s invitation stated that if invited he might be “tempted to take the opportunity of showing that he regarded himself here to celebrate the victory of civilisation over the Anglo-Saxons!”

Another major objection put forward in point 6 was that as French commemorations relating to Hastings were taking place only in Normandy and not nationally, it would be inappropriate for Britain to invite the French president to its own events. It was recommended that an alternative representative from the French republic be found and Monsieur Jean de Broglie was named as a suggested candidate.

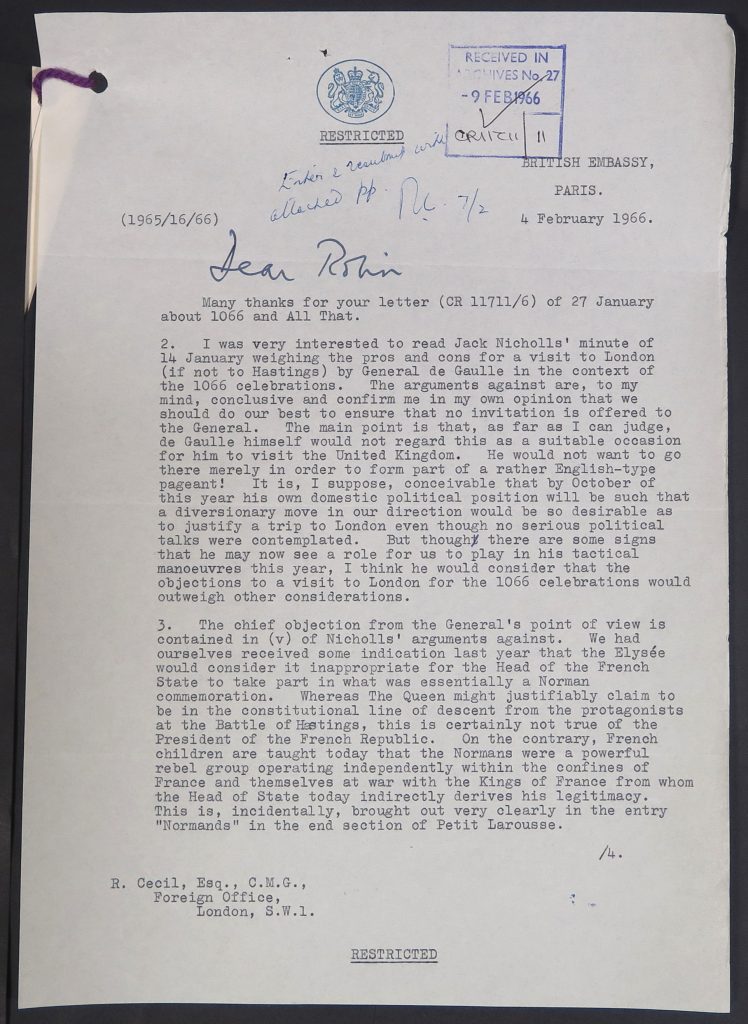

The British ambassador in Paris, Sir Patrick Reilly voiced his agreement to this last objection in a letter of the 4th February, 1966 (found in FO 924/1630) in which he highlighted the regional character of French 1066 commemoration events. He informs his colleagues that “the Elysee would consider it inappropriate for the head of the French state to take part in what was essentially a Norman commemoration. Whereas the queen might justifiably claim to be in the constitutional line of descent from the protagonists at the battle of Hastings, this is certainly not true of the president of the French Republic.”

He considered Prince Jean de Broglie a viable alternative especially as he was from Normandy and was heading up French commemoration events. Nevertheless Reilly did consider that his presence may provide “a mild political flavour” given that he was also recently appointed Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. However he reassured that there would be no risk of embarrassment “even if we were having quite a row with the French about NATO at the time.”

An invitation was later sent to de Broglie to attend a ceremony service at the battle site near Hastings and a banquet hosted by the mayor of Hastings on 14th October 1966 and with relief to all concerned was accepted - the dilemma about the representative for the French Republic was resolved.

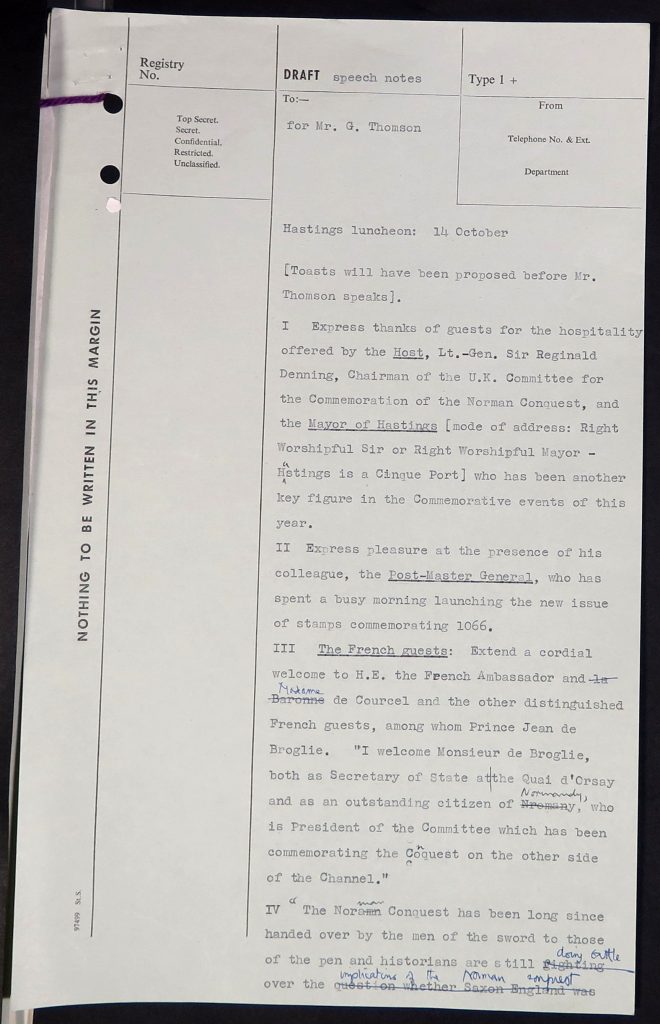

The events on 14 October 1966 at the battle site included a commemoration service led by the Dean of Battle, an unveiling of a commemorative plaque complete with a guard of honour, a band from the 1st battalion Royal Staffordshire Regiment, and a banquet lunch. Details of the preparations for the day’s events can be found in FO 924/1638.

Included in the file are the annotated speech notes to be delivered at the banquet by the right honourable George Thompson MP, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. The contents of the speech say a lot about the context in which the anniversary of 1966 was commemorated. It had only been 21 years since the end of WWII and George Thompson was keen to highlight the enduring Anglo-French comradeship demonstrated in the war and especially on the beaches of Normandy. He made the point that, as in the year 1066 when William crossed the channel for England, the weather played a crucial role in the timing of the allied invasion of Normandy almost 900 years later.

Perhaps the most interesting and final thing to note is the insight into why French attitudes to commemorating the battle of Hastings contrast with the more national character of those in Britain.

Returning to Reilly’s letter of 4th February, he informs his colleagues that “French children are taught today that the Normans were a powerful rebel group operating independently within the confines of France themselves at war with the kings of France from whom the head of state today indirectly derives his legitimacy.”

France in the 11th century was far more provincial and less centralised with autonomous regions such as Normandy, Brittany and Aquitaine governed by semi independent rulers including the Norman dukes who frequently challenged French royal authority. French kings only began to emerge as undisputed sovereign of their territories from the 13th century onwards.

This explains why the battle of Hastings is not stamped onto the consciousness of the French nation as an event of national importance in the same way that it is in Britain. In contrast, for the countries of the British Isles, the battle of Hastings changed the fundamental course of their history and its impact would resonate down the centuries.

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.