Since this article was written, Prof. George Jones OBE has sadly passed away. He was a foremost authority on the office of Prime Minister and long-term contributor to the history of government blog. This article is published as a tribute to him.

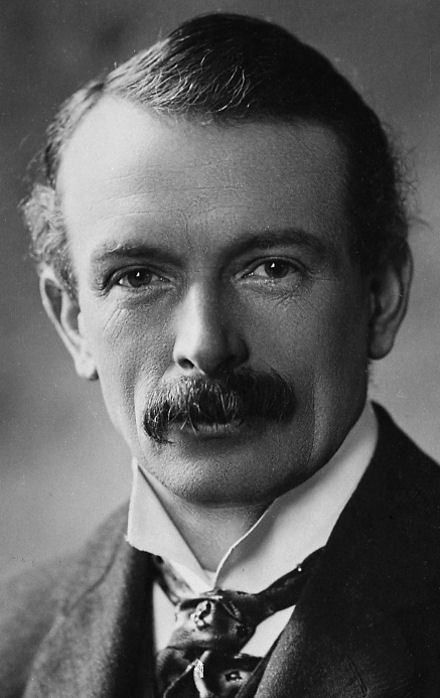

A century ago the first experiment in attaching a team of specialised policy advisers to the office of Prime Minister was in its early stages. In our previous blog on this subject we described how David Lloyd George formed the Prime Minister’s Secretariat or ‘Garden Suburb’ in January 1917, shortly after his arrival at No.10. It would prove to be a precursor to an administrative model that continues to function today.

Assessment

The key purpose of the Garden Suburb was to support Lloyd George in the conduct of the First World War. It represented a challenge to the way in which government had operated previously, based on an enhanced policy role for the Prime Minister. But would it still be needed once hostilities had come to an end?

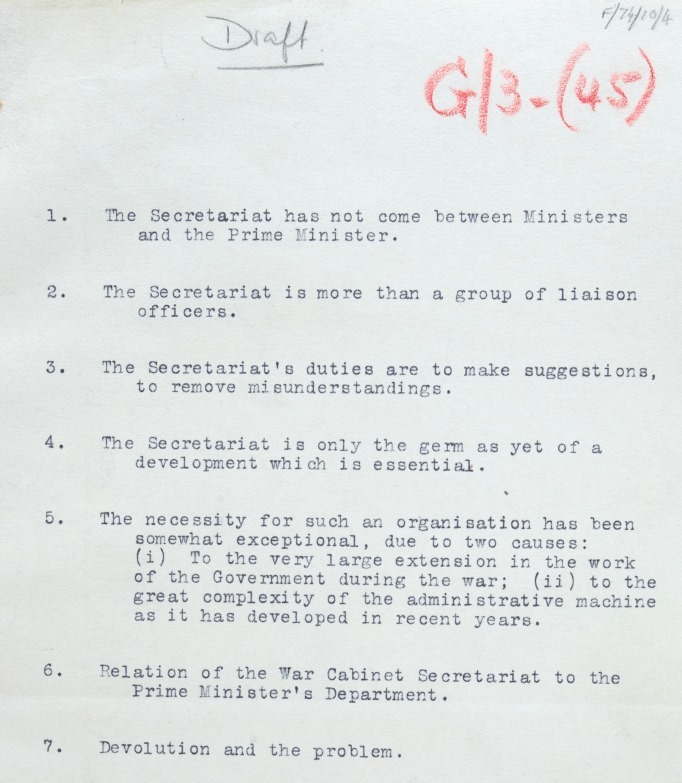

In a draft note from March 1918 the head of the Garden Suburb, W. G. S. Adams, provided an overall assessment of the body. He emphasised the idea that:

‘[o]ur relationships with the Departments have been very free and informal, the whole object of the relationships being to help the departments in getting matters to the attention of the Prime Minister when they were of urgency, and, as far as possible to arrange and prevent matters from pressing upon the Prime Minister. It has, I think, been found possible to do a great deal in the way of securing settlement on points upon which there was doubt, if not dispute, and of helping to bring people and bodies together who would benefit by closer relationship with one another in their work.’[1]

Judging the Garden Suburb a success, Adams wanted it to be expanded in the future:

‘[t]he Secretariat is only as yet a first tentative step in the direction of a development which is, I believe, necessary in the present complex working of Government, and in the burden of work which falls on the Prime Minister. The necessity for such an organisation has been somewhat exceptional, due to two causes: (1) To the very large extension in the work of the government during the war, and (2) to the great complexity of the administrative machine as it has developed in recent years.’

Adams’s conclusion was ‘that there should be a Prime Minister’s Department created.’[2] Such an entity would potentially have posed a threat to the Cabinet system, to departmental interests, and to the established Civil Service. But it never came about. At the end of the First World War the Garden Suburb was scaled down. Soon Lloyd George was supported by only one policy adviser, Philip Kerr, a foreign-affairs specialist, rather than a team of around five as previously.

After Lloyd George

Lloyd George lost power in 1922 and his approach to government acquired the reputation of being detrimental to good practice. The prime ministers who succeeded him, Bonar Law and Stanley Baldwin, were reluctant to be perceived as following his example. But another crisis, similar to that which had first inspired the Lloyd George innovation, drove a revival of his approach.

Winston Churchill – who had observed the Lloyd George governments from the inside as a minister – became premier in 1940 in the Second World War. The administrative reorganisation he pursued at this point bore clear similarities to the experiments of his predecessor. One of the Churchill innovations was the establishment of a team – the Statistical Section – attached personally to the Prime Minister, charged with giving him oversight of the deployment of resources for the war effort. At its head was Frederick Lindemann (who became Lord Cherwell in 1941), an Oxford physicist and good friend of the Prime Minister.

The Policy Unit

Another reviver of the Lloyd George idea was the Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson, who had served as a temporary civil servant in the Cabinet Office during the Second World War and witnessed the Churchill experiment. In 1964 Harold Wilson established a small group of aides to support him on policy, led by his friend, the Hungarian Oxford economist Thomas Balogh. Wilson lost power in 1970 and there was a reaction against his methods, as there had been following the fall of Lloyd George - by the successor to Wilson at No.10, the Conservative Edward Heath. But when Wilson became Prime Minister again in 1974 he formed the Policy Unit. Under the headship of Bernard Donoughue, an academic from the London School of Economics and Political Science, it shadowed a range of government business on behalf of the Prime Minister. At first formed wholly of staff drawn from beyond the permanent Civil Service, the Policy Unit can be seen as a continuation of the tradition starting with the Garden Suburb. The difference is that it has survived largely uninterrupted to the present.

No ‘Department of the Prime Minister’ has come into being. But the view Adams expressed nearly a century ago that the demands of government would necessitate extra support for the Prime Minister has been proven correct.

This blog is authored by Dr. Andrew Blick and Prof. George Jones. We are grateful to the Parliamentary Archives for allowing us to reproduce material from the Lloyd George Papers.

Further reading:

Andrew Blick and George Jones, Premiership: the development, nature and power of the office of the British Prime Minister (Imprint Academic, Exeter, 2010); At Power’s Elbow: Aides to the Prime Minister from Robert Walpole to David Cameron (Biteback, London, 2013).

Peter Hennessy, Whitehall (Pimlico, London, 2001).

John Turner, Lloyd George’s Secretariat (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2009).

Ian Wilson, Churchill and the Prof (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1997).

Footnotes:

[1] Parliamentary Archives, Lloyd George Papers, LG/F/74/10/4, pp.2-3.

[2] Parliamentary Archives, Lloyd George Papers, LG/F/74/10/4, p.5.

Keep tabs on the past.Sign up for our email alerts.

1 comment

Comment by Robin S. Taylor posted on

Instead of a "Department of the Prime Minister" could we not call it "The Prime Ministry"?