Seventy-five years ago today, on 13 September 1944, a Dakota aircraft, with an escort of 45 Spitfires, flew across the English Channel towards Paris. The plane carried the new British Ambassador to France, Alfred ‘Duff’ Cooper. The liberation of Paris from German occupation in August 1944 meant a chance to reopen the British Embassy which had been closed since June 1940. With the provisional government of General Charles de Gaulle now in the French capital, it was a priority for the British to re-establish a presence in the city.

The new Ambassador

Cooper was returning to his original profession. He had begun his career as a diplomat before pursuing a life in politics. Since January 1944, he had been the British representative to the French Committee of National Liberation, based in Algiers, led by de Gaulle. He was an ardent Francophile, spoke fluent French and steeped in the history and culture of the country. In Algiers, he had developed good relationships with senior French ministers and officials. As a Conservative politician, he also had a direct line to British Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden.

Duff’s wife, Diana Cooper, one of the leading society figures of her day, accompanied her husband. He argued that a member of the Foreign Service was always more effective with his wife and,

having no batman, no Army cooks, laundries etc in these days of chronic servant difficulties, very often depends on his wife to keep body and soul together.

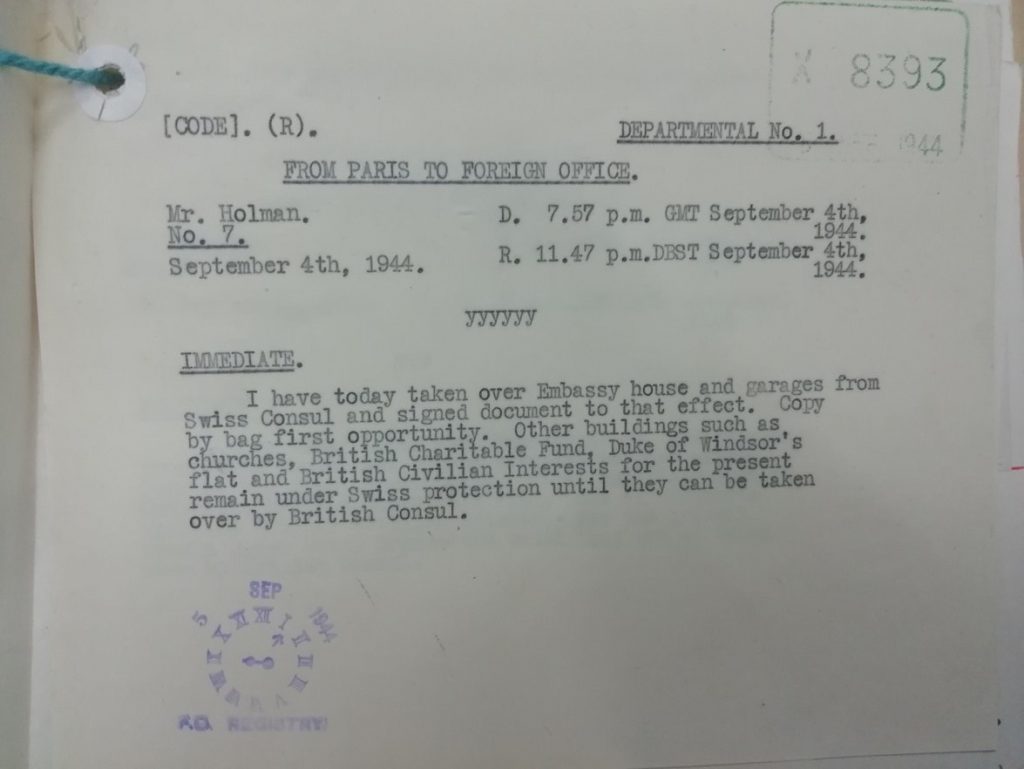

They landed at Le Bourget airport and were met by an advance party of Embassy staff, headed by Adrian Holman, the Embassy Counsellor. Holman had arrived earlier in the month with the combination codes to the safes and 50,000 francs in cash. He took possession of the building from the Swiss consul who, as the protecting power, had taken responsibility for it during the occupation.

The Embassy was swept for any listening devices left behind by the Germans but none were found. In fact, the Germans had left the building untouched. When the embassy was vacated in 1940 the doorkeeper, William Chrystie, was left in charge. One day in 1941 Herman Goering turned up, looking for a suitable house, and demanded admittance. Chrystie replied the building was protected under international law and ‘you enter it over my dead body,’ before shutting the door in his face. He was subsequently arrested and imprisoned for 5 months, but the Germans never occupied the building.

After leaving the airport, the Ambassador’s first act was to lay a wreath on the tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the Arc de Triomphe before going to the Embassy.

Whilst the building was in good condition it would be a month before it was inhabitable as there was no water or electricity and the building resembled a flea-market. It was filled with furniture and other possessions left behind by families fleeing the Germans. Diana recalled rooms piled high with ‘pianos, hatstands, bureaux, bath-mats, sponges, bottles, good and bad pictures, boxing gloves and skates, clouds of moth, powder of woodworm'.

It was not long before the Embassy was up and running. As well as the counsellors and secretaries handling political and economic work there was a full complement of administrative staff: an archivist, typists, consular staff, cypher officers, personal secretaries, telephone operators, financial and commercial advisers, and a press attaché.

There was much discussion over the appointment of a labour attaché. Cooper went so far as to consult the Minister for Labour (and future Foreign Secretary) Ernest Bevin, to find the right candidate.

The Foreign Office also arranged for:

- 4 cars and drivers (including a big Daimler)

- 2 10-tonne trucks of coal

- a wireless transmitter

- and an operator to provide secure communications with London

The role of the Embassy

In those early months, the Embassy was operating in a testing environment. Large parts of France were still a war zone under the control of the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force. The outcome of the war was by no means certain and at Christmas there was minor panic when the German offensive in the Ardennes began to push Allied forces back. The city itself was recovering from the shock of occupation, and cinemas and theatres, cafes and restaurants were shut because of electricity and food shortages.

But the Embassy had an important role to play. Its primary task was political, the maintenance of good bilateral relations. This was no mean feat given the personal animosity that existed between de Gaulle and Prime Minister Winston Churchill. According to Cooper, de Gaulle frequently appeared to seek out real or imagined insults at which to take offence.

Matters were not helped by the fact that the US President delayed recognising de Gaulle’s government for 2 months after liberation, during which time the General refused to see Cooper. It was November before he formally presented his credentials. However, beyond the man-management, Cooper believed in a Franco-British alliance as a basis for wider Western security. His efforts came to fruition in 1947 with the signing of the Treaty of Dunkirk.

Churchill’s first visit since liberation came in November 1944 for the Armistice commemoration. The Embassy hosted a dinner party for both leaders, their foreign ministers, and the US, Russian and Canadian ambassadors.

Fears of an assassination attempt from Germans or disgruntled Vichy still hiding in the capital proved unfounded. Churchill and de Gaulle rode through the city in an open top car and walked down the Champs-Elysées to the adulation of cheering crowds.

Social life

Just as important was the social function the Embassy played. Under the Coopers, the Embassy became a draw for intellectual and artistic circles as well as political decision-makers. It helped that the building was one of the few in Paris to be heated, during what was a particularly cold winter, and well stocked with government-supplied food and alcohol.

The Coopers were seasoned hosts and, as one historian put it, they provided ‘a rare mixture of the grand diplomatic style and the Bohemian intellectual’. Their entertaining was not without controversy. There was criticism that the Embassy was entertaining collaborators, even though the guest list was usually shown in advance to de Gaulle’s Chef de Cabinet. Nevertheless, the pair provided a glamour that put the Embassy at the centre of Parisian social life.

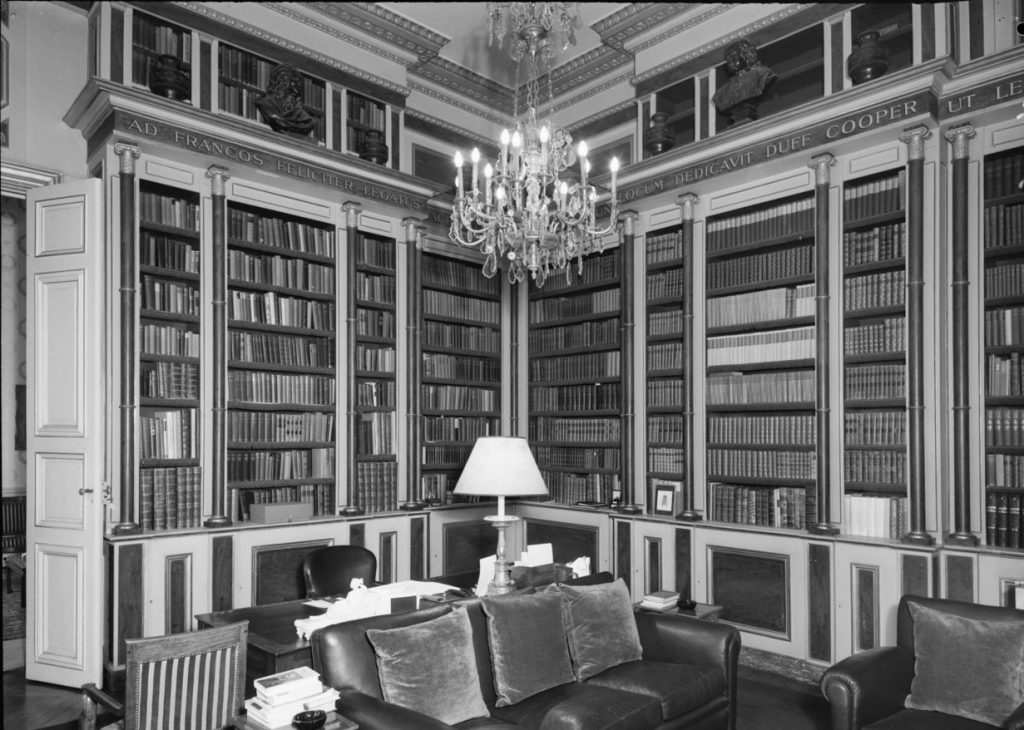

Finally, Cooper left a physical legacy to the Embassy in the form of a library, which he persuaded a reluctant Ministry of Works to construct and also filled with his own books. Despite difficulty in sourcing materials, due to post-war shortages, the end result was impressive. The library now provides a lasting reminder of Duff Cooper’s tenure as Ambassador.

Keep tabs on the past: sign up for our email alerts

Follow our Foreign & Commonwealth Historians on Twitter @FCOHistorians

1 comment

Comment by Alys blakeway posted on

Diana Cooper refused to leave when her time was up and hung out in a flat at the Embassy gates, conducting a busy social life and annoying her successor. See Nancy Mitford 's Don't tell Alfred.