The outbreak of the Second World War is often portrayed as inevitable. Yet over the weekend of 1 to 3 September 1939, there was a flurry of communication, suggesting that not everyone believed war was unavoidable. The armed forces of a number of countries were on alert. So was there a real chance of preserving peace or was it just a matter of going through the diplomatic motions?

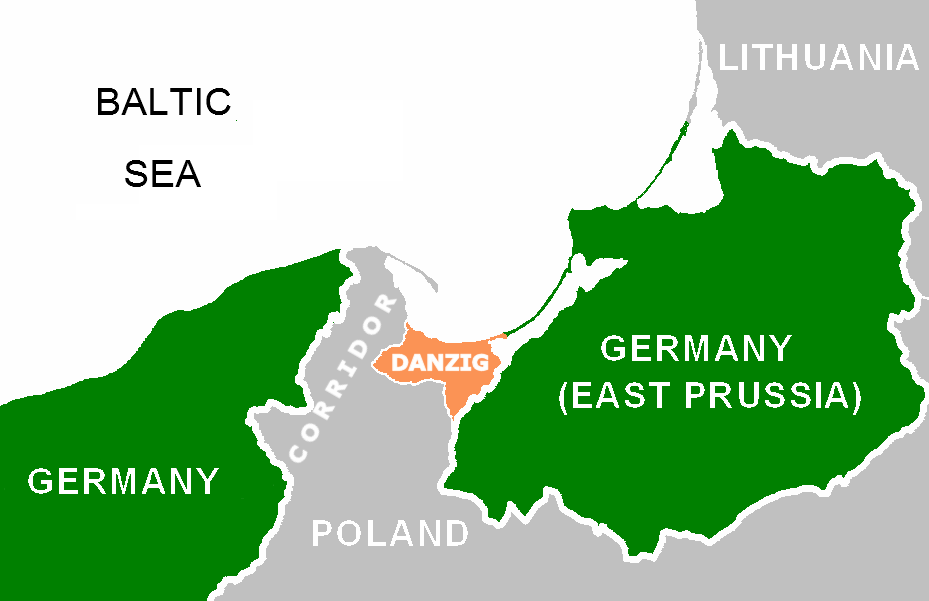

The previous March, following the German invasion of Czechoslovakia, Britain had given a guarantee that if Poland was attacked, they would come to its aid. In August, Hitler demanded that the Danzig Corridor, formerly part of Germany but now part of Poland, be yielded to Germany. The Poles refused, as they had done 3 times previously. They feared that to do so would result in the same outcome experienced by Czechoslovakia; invasion and subjugation.

Initially, the British Government was unconcerned by Hitler’s demands. Previous difficulties had been solved diplomatically, most recently at Munich in September 1938. However, since March concerns had grown over Hitler’s true ambitions.

Friday 1 September

At 4:45am, Germany invaded Poland. Later that morning, Hitler addressed the German parliament falsely claiming that this was in retaliation for Polish attacks. The Polish Government turned to France and Britain to honour their commitments.

From the British side telegrams were dispatched between London, Rome, Paris, Berlin and Warsaw. A well-connected Swedish engineer and amateur diplomat called Birger Dahlerus was also trying to mediate between Britain and Germany. His efforts might have been less welcome if the British Government knew how strong his connections were to Hermann Göring, President of the German Parliament.

The debate in the British Parliament was not particularly anti-German, somewhat surprisingly considering the propaganda of the First World War. Just after 6pm, the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, declared:

We have no quarrel with the German people, except that they allow themselves to be governed by a Nazi government.

Parliament agreed with the Government’s stance, although some felt Britain should take a stronger position.

The British and French governments agreed a text to be handed to the Germans. Their ambassadors to Berlin tried to make a joint appointment to deliver it but were unsuccessful. At 9pm, the British Ambassador, Nevile Henderson, handed a copy of the agreed text to the German Foreign Minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop. It stated that Britain and France did not accept Germany’s actions towards Poland. If Germany did not suspend their actions and agree to promptly withdraw from Poland, the UK would fulfil their obligations to Poland. Henderson, despite pressing for an immediate response as instructed, received none. The French Ambassador met von Ribbentrop at 10am with the same outcome.

Henderson and von Ribbentrop were barely civil to each other, which reflected their relationship. Henderson’s relationship with Göring was more cordial, but Henderson’s appointment to his post had been partly based on his ability to get along well with dictators.

Saturday 2 September

The lack of response to the previous day’s message initially gave the British Foreign Secretary, Viscount Halifax, hope. He wondered whether the delay could mean that Hitler was considering the ultimatum. As the day progressed, his hope faded. The Counsellor at the German Embassy in Paris recognised that France would stand by their treaty obligations to Poland; they would not change position. Basing his views on intercepted British diplomatic correspondence, supported by the opinion of the German Ambassador in London, von Ribbentrop doubted that Britain would act. This failure to recognise the British position accurately later caused Ribbentrop to lose favour with Hitler.

At 5pm, the British and French Foreign Ministries discussed giving Hitler a time limit to respond to their démarche. The Poles were in favour of this idea. Mussolini had furthermore offered to host a conference to resolve the Danzig matter. The French and British discussed whether this should be conditional on German withdrawal from Poland. Halifax had wondered whether Mussolini’s offer had delayed a German response.

At 6:30pm the British and Italian Foreign Ministers spoke, the latter acting as an intermediary with Hitler. Was the British communication an ultimatum? No, as Henderson had said, it was a warning. Could Hitler have a response about the conference by midday on 3 September? Britain did not favour a conference whilst German troops were on Polish territory. The French held the same position.

With so much at stake, there were telephone calls and meetings late into the evening and telegrams sent throughout the night, not just in Berlin, but capital cities all over Europe.

Sunday 3 September

At 12:25am and again at 5am the Foreign Office sent telegrams to Henderson instructing him to seek a meeting with Ribbentrop at 9am. The message: unless the British Government received assurances by 11am that German aggression in Poland had ceased, Britain and Germany would be at war. Henderson and Ribbentrop actually met at 9:15am.

At 10:30am, the British War Cabinet assembled. They had 3 different telegrams prepared to send to the service chiefs, depending on the response from Berlin. Would Germany agree to withdraw from Poland, would war be declared or would it merely be postponed?

At 10:50am, Dahlerus phoned the British Foreign Office indicating that the German reply was on its way, but might not arrive by 11am. At 11:20am, Henderson met von Ribbentrop at the latter’s request. The 11 page response and the meeting reaffirmed that Germany refused to leave Poland.

At midday, the French Ambassador called to hand over the text to von Ribbentrop. He was kept waiting whilst the ceremonial presentation of the new Russian Ambassador took place. At Berlin time (11:15am UK time), Chamberlain addressed the nation and announced Britain’s declaration of war. In Berlin, the French Ambassador waited and handed over the text at 12:20am with a deadline of 5pm. He received no response. Germany was once again at war, but not the limited war Hitler had intended at this stage against an Eastern neighbour.

Keep tabs on the past: sign up for our email alerts

Follow our Foreign & Commonwealth Historians on Twitter @FCOHistorians